The role of ego in academic profile services: Comparing Google Scholar, ResearchGate, Mendeley, and ResearcherID

Academic profiling services are a pervasive feature of scholarly life. Alberto Martín-Martín, Enrique Orduna-Malea and Emilio Delgado López-Cózar discuss

Academic profiling services are a pervasive feature of scholarly life. Alberto Martín-Martín, Enrique Orduna-Malea and Emilio Delgado López-Cózar discussthe advantages and disadvantages of major profile platforms and look at

the role of ego in how these services are built and used. Scholars

validate these services by using them and should be aware that the

portraits shown in these platforms depend to a great extent on the

characteristics of the “mirrors” themselves.

The model of scientific communication has recently undergone a major

transformation: the shift from the “Gutenberg galaxy” to the “Web

galaxy”. Following in the footsteps of this shift, we are now also

witnessing a turning point in the way science is evaluated. The

“Gutenberg paradigm” limited research products to the printed world

(books, journals, conference proceedings…) published by scholarly

publishers. This model for scientific dissemination has been challenged

since the end of the twentieth century by a plethora of new

communication channels that allow scientific information to be

(self-)published, indexed, searched, located, read, and discussed

entirely on the public Web, one more example of the network society we live in.

In this new scenario, a set of new scientific tools are now providing

a variety of metrics that measure all actions and interactions in which

scientists take part in the digital space, making some hitherto

overlooked aspects of the scientific enterprise emerge as objects of

study. In the words of Jason Priem

the First Revolution promoted the homogeneity of outputs (through

academic journals, the main communication channel), and the Second

Revolution promotes the diversity of outputs. We can draw a comparison

between those revolutions and the changes that are taking place in the

field of scientific evaluation: the First Revolution promoted the

homogeneity of performance metrics (through the Impact Factor, the “gold

standard” of scientific evaluation), and the Second Revolution promotes

a diversity of metrics (h-index, altmetrics, usage metrics). The

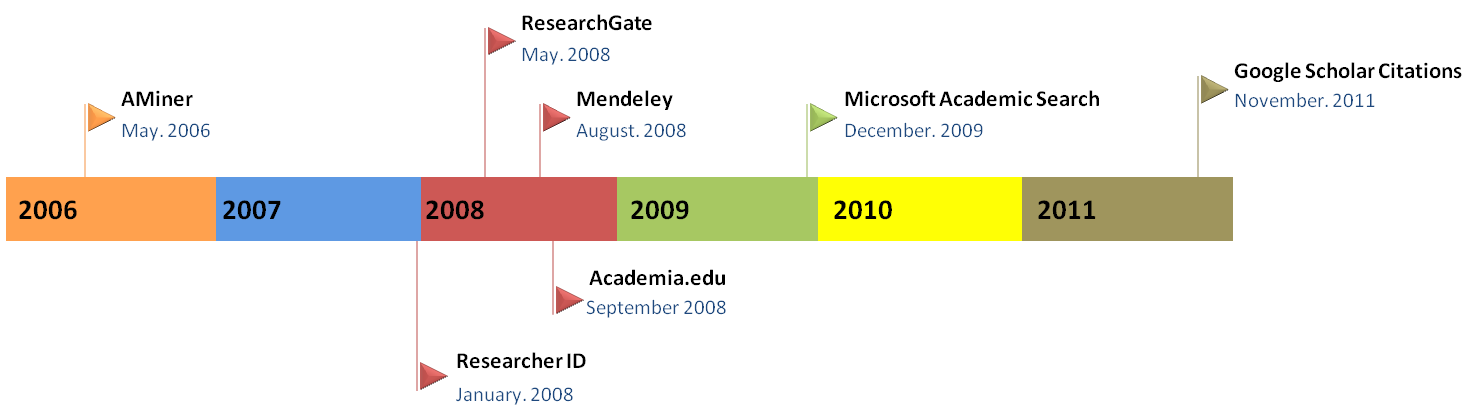

emergence of academic profiling services (most of them created in 2008)

was a collateral consequence.

Because each of these tools focuses on fulfilling a different set of

needs, caters to a specific audience (diverse communities), and provides

a variety of different metrics, it stands to reason that they should

reflect different sides of academic impact. Each platform becomes then a

mirror reflecting the likeness of the communities that use it.

Recently, we set out to radiograph the discipline of Bibliometrics,

not only trying to identify the core authors, documents, journals, and

the most influential publishers in the field, but also comparing the

diverse portraits shown by each platform, with special attention to the

one offered by Google Scholar Citations. We collected data for a sample

of 814 researchers who work mainly or incidentally in the field of

Bibliometrics. These data can be browsed in the website Scholar Mirrors, and an analysis of the results can be found in this working paper.

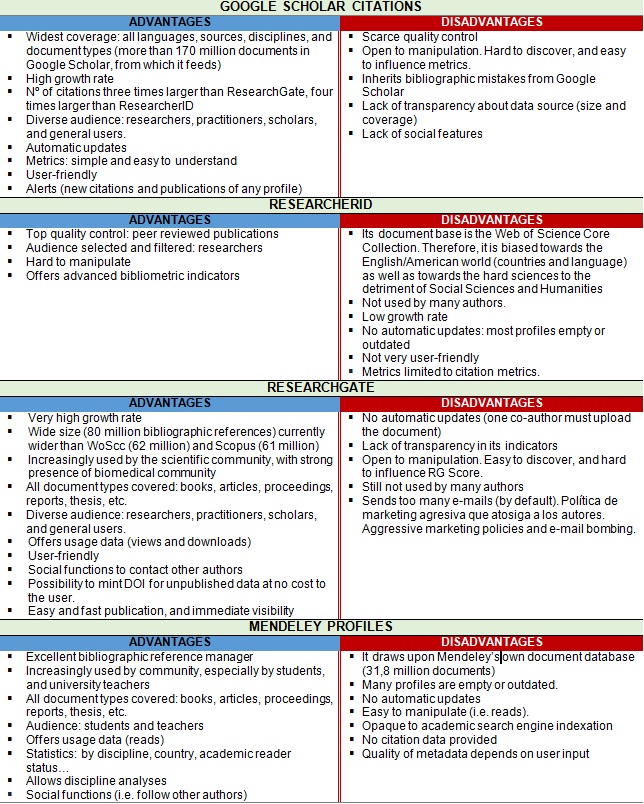

During this exercise we isolated some of the main features of these

academic profiling services (Google Scholar Citations, ResearchGate,

Mendeley, and ResearcherID) in terms of their general advantages and

disadvantages, which are summarized below in Table 1.

TABLE 1: COMPARISON OF DIFFERENT ACADEMIC PROFILING SERVICES

Each academic profile platform offered distinct and complementary

data on the impact of scientific and academic activities as a

consequence of their different user bases, document coverage, specific

policies, and technical features. Not all platforms have a homogenous

coverage of all scientific disciplines. Likewise, their user bases

aren’t uniform either. Researchers should be aware that the bibliometric

portraits shown in these platforms depend to a great extent on the

individual characteristics of the “mirrors” themselves.

Google Scholar Citations profiles draw upon

the vast coverage of Google Scholar (giving voice to all disciplines,

languages, countries; academics and professionals) at the cost of a

little accuracy (errors in parsing citations or authorship) and with an

austere approach (few indicators, and little user interaction).

Nonetheless, it offers the most advanced management system for versions

and duplicates.

Regarding ResearchGate, the great amount of

documents already uploaded by a growing user base (especially from the

biomedicine community) supports the usefulness of some of its indicators

(especially Views and Downloads, now combined into Reads). However, the lack of transparency

compromises its reliability. Likewise, unannounced changes in some of

its key features make this platform unpredictable at the moment.

Mendeley, despite being an excellent social

reference manager, offers the most basic author profiling capabilities

of all the platforms we analysed, although we should acknowledge the

usefulness of the Reader metric. The term used to define this metric is,

however, misleading, because it doesn’t accurately reflect the nature

of the metric. Lastly, the fact that profiles aren’t automatically

updated makes the system completely dependent on user activity. This

fact strongly limits the use of Mendeley’s profile page for evaluating purposes.

ResearcherID does not offer automatic

profile updates either. As a result, a great percentage of profiles have

no public contributions listed in their profile (34.4% in our sample of

bibliometricians, which should be the ones who are most aware of these

tools). Moreover, we found errors in citation counts inherited from the

Web of Science. A word of warning: the Web of Science also makes

mistakes.

At any rate, the growth of academic profiling services is unstoppable, and practices like the aggressive marketing used by ResearchGate

fuel the ego that dwells in every researcher through the systematic

e-mail bombing directed to the Narcissus that lives inside of us. The

potential positive effects are clear: new channels of information and

new collaboration tools. However, this road might also lead us to look

ourselves in the scholar mirror every day, and there lies the path to

the Dark Side.

Paraphrasing Bill Clinton’s famous quote for the 1992 North American presidential campaign: “it’s the economy, stupid!”

we could now state the following: it’s not the collaboration; it’s the

ego, stupid! Ego moves Academia. These new platforms, whether they are

integrated in other products or not, will be massively used by

universities, research institutions, and national funding agencies to

evaluate scholars, because scholars are validating them by using them

massively. Hence, we should not conclude without warning about the

dangers of blindly using any of these platforms for the assessment of

individuals without verifying the veracity and exhaustiveness of the

data.

This blog post is based on a working paper which can be found here. All the data obtained for each author profile and the results of the analysis can be found at Scholar Mirrors.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the

position of the LSE Impact blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

About the Authors

Alberto Martín-Martín is a PhD Candidate in the field of bibliometrics and scientific communication at the Universidad de Granada (UGR).

Enrique Orduna-Malea works as a postdoctoral researcher at the Polytechnic University of Valencia (UPV).

Emilio Delgado López-Cózar is a Professor of Research Methods at the Universidad of Granada (UGR).

Impact of Social Sciences – The role of ego in academic profile services: Comparing Google Scholar, ResearchGate, Mendeley, and ResearcherID

No comments:

Post a Comment