The current state of academic publishing is something we should all be thinking about

,

given that it’s a means of disseminating the knowledge generated by

academic research — much of which is publicly funded yet inaccessible to

the public. Publishing is also significant because of the key role it

plays in academic careers, where it serves as a gatekeeping mechanism.

Changes to academic publishing both reflect, and contribute to,

broader trends within academe; and they point to a range of critical

questions. Within the contexts and constraints of established

institutions and practices, what possibilities are opened up by recent

technologies and new organisational forms? How could publishing change

in (and differ across) the various academic areas and fields? How might

the increased competition for academic jobs, and the smaller proportion

of scholars with permanent positions, affect publishing and associated

labour? Can we maintain the accessibility and quality of publications

and the process of peer review while also ensuring compensation for the

work involved? What about digital publication and circulation – will

(paywalled) journal publishing eventually become obsolete?

This post explores some of those questions by way of an interview with

Professor Martin Paul Eve,

who is an all-round expert on, and active promoter of, open access

academic publishing. Professor Eve is chair of literature, technology

and publishing at Birkbeck, University of London, and the author of

Open Access and the Humanities: Contexts, Controversies and the Future.

Among many other things,

Professor Eve also gave evidence to the U.K. government’s business,

innovation and skills committee inquiry into open access, in 2013, and

with Dr. Caroline Edwards he is a co-founder of the

Open Library of the Humanities

(OLH), in which 16 Canadian institutions are already participating. The

following interview focuses on OLH and on the issues of access to

knowledge (in the form of peer-reviewed research) that underlie its

creation.

Dr. Martin Paul Eve.

could you provide a bit of a description of what it does and how it

works?

The Open Library of Humanities is a charitable, not-for-profit, open

access publisher of peer-reviewed humanities research material that I

co-founded with my colleague Dr. Caroline Edwards. The OLH currently

publishes (or financially supports) 18 journals and in our first year of

operation we made over 900 scholarly articles available at no charge to

readers.

Unlike other open access publishers, though, the OLH has a different

economic model. In a move to abandon subscriptions so that there is no

cost to read academic research work on the internet, many publishers are

turning to so-called Article Processing Charges (APCs); a fee to be

paid by the author, their institutions, or their funders. This is not a

fee to bypass peer review, but rather a fee to cover the publisher’s

labour (and surplus/profits). It is a substitution for subscription

revenue.

In our disciplines, however, it is far harder to see where this money

will come from (Taylor & Francis for instance has an APC of about

$2,000). Our model works differently. Instead of asking authors or

funders to pay when work is accepted, we have over 200 libraries paying

us an annual amount that

looks like a subscription. The change

though is that with the money from that fee, we make all our work openly

available. So yes, even if libraries don’t pay, their academics can

submit and read the work. We know, though, that this is not how

libraries and universities think. Universities should exist for the good

of society, not for exclusionary gain. The fact that so many libraries

have supported this non-classical economic model so that research work

can be broadly accessible is the proof.

You mentioned in another interview that this idea was

coalescing at the end of 2012/early 2013, as part a broader discussion

about scholarly publishing; three years later, OLH has been running for

over a year and has participants at more than 200 institutions. How did

you get started with a project of this size, let alone get it running

within such a short period — and especially when the process involves so

much consultation and buy-in from so many different groups?

I often wonder to myself: were I able to go back in time and warn my

previous self how much work and how difficult the whole thing would be,

would I still do it? I like to think the answer is “yes” because I

believe in higher education and that research work should be accessible

to anyone who is interested. But it is hard to say when speaking in such

hypothetical terms.

We began by simply floating the idea online of creating something a

bit like the Public Library of Science (PLOS) in the humanities. When I

put up an initial web page, we had over 200 emails overnight from

interested parties, so the demand seemed clear. We also realised early

on, though, that we’d need to play the prestige game very carefully. The

whole academic system of certification and accreditation is built on a

symbolic economy of prestige. This makes it very hard for new players to

enter the arena since they do not yet have a track record and many

academics fear that they will lose out on career progression (or even

jobs) if they do not play the game that hiring panels expect.

That said, some early supporters gave us a boost. We’re immensely

grateful to David Armitage, for instance, the Lloyd C. Blankfein

Professor of History at Harvard, who said of the OLH that “there is

hardly a more important project in train for scholarship in the

humanities today.” We also assembled committees of high-profile

academics to ascertain what they felt would be needed to make an idea

like OLH work. And we listened and we structured the platform around the

advice we received. For instance, the first version of the OLH was

going to be based on Article Processing Charges, as is PLOS. But the

committees baulked at this and so we had to design a new, untested model

for the ongoing economic support of academic journals. We also had to

balance the desires of hard-line open access enthusiasts against a

distaste for full open licensing among some of our disciplinary

communities. We had to handle the more radical thinking of some

technologists against the traditions of the humanities and the need to

ensure their continuity.

We also had to work out how to establish and govern a charitable

company; something with which I was totally unacquainted before we began

the enterprise (I feel I should here mis-cite Bones McCoy from

Star Trek:

“Damn it Jim, I’m an academic not a businessman”). Generous support

from the University of Lincoln; Birkbeck, University of London; and the

Andrew W. Mellon Foundation made this all possible. Indeed, we spent

those setup years travelling the world and telling academics,

librarians, societies, and publishers what we wanted to do and gaining

their trust, support, and feedback.

As a result we managed to go from rough idea at the end of 2012/2013

to a platform launch in September 2015. That’s not a bad timescale but

we did nonetheless receive criticism that it was too slow (one person

wrote, paraphrasing, that “the OLH has to-date not published a single

article”). And this is the dilemma. If you spend time planning things,

people criticize you for taking too long. If you rush into it, people

criticize you for not planning.

You’ve said that “Cooperation can solve the budget crisis in

scholarly communications where competition has failed us.” How does the

OLH model (and maybe open access overall) function as cooperative?

The term “cooperative” has different meanings in different contexts.

There’s a formal organizational structure called a “cooperative” that

refers to co-ownership of an enterprise by its employees. I didn’t quite

mean that but rather the underlying principle of working in concert

rather than relying on free-market competition.

To explain this, I have to give a brief background to the economics

of scholarly communications. Since 1986, according to ARL statistics,

the cost for each institution of subscribing to the full range of

journals that its academics and students require has risen by an

estimated 300 percent

above inflation. There are many reasons

for this. One is that the mass expansion of higher education has led to

greater publication volume. However, there is also the matter of vast

profits and quasi-monopolistic practices among large publishers.

Indeed, the largest publisher of scientific journals, Elsevier (RELX

Group), makes an approximate 35 percent profit. As I’ve pointed out

before, this is double the profit rate of oil and pharmaceutical

companies. Clearly – despite the efforts of Elsevier’s supporters to

equate such exorbitant profits with charitable surpluses (the most

frequent comeback I get to the preceding fact is: “even OLH has to make a

surplus”… Yes, but it’s hardly the same as a 35 percent profit!) –

something is going very wrong with the market here.

So why hasn’t free-market competition solved this problem? Well,

goods in the scholarly communications market (academic journal articles

and books, for example) are not substitutable goods. When an academic

needs to read a specific piece of work,

only that article or

book will do because the content is, usually as a precondition, unique

and novel. Companies like Elsevier who own the copyright on up to 40

percent of the supply in certain disciplinary spaces know that academics

need the work they possess. So there is no competition in this sense;

unique non-substitutable goods that are required for academic work are

for sale at whatever rate the owner demands.

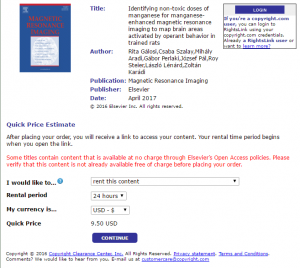

Open access and article processing charges do not necessarily resolve

the crisis of library budgets, though. Hybrid open access refers to the

conditions where publishers run a journal as a subscription entity but

allow authors to pay a charge to make a specific article openly

available. The problem here is that, without offsetting of the amount

paid, the charges just mount and mount on top of subscription revenue.

Because the people paying – the library – are not the same as the people

submitting and reading – the academics – there is little sensitivity to

such pricing from those who have the most agency within the system.

For me, this all amounts to a failure of scholarly communications

practices to act like a market. And perhaps we don’t want it to be one.

This is why I proposed cooperation as a way in which library acquisition

staff can escape the failure of market competition. By pooling

resources – as does the OLH by gathering small amounts from a moderate

number of libraries – on a not-for-profit basis, we see a better use of

budget than market competition was able to deliver. Indeed, across our

200 supporting institutions, we estimate that the approximate average

paid was $1,000. This works out at just $55 per journal per institution.

Alternatively, this is $1.10 per institution per article (many of the

articles in our first year comprised cheaper back-content import

though). However, if we flip this around and focus on the 118,686 unique

users who visited article pages in our first year, this is just $0.008

per institution per reader. And this gets cheaper as more institutions

join.

That’s why I advocated for a form of cooperation. Do not focus on the

problem of “free riders” and the fact that even if one pays, others get

access for nothing. Instead focus on what such non-classical economic

thinking can actually deliver.

Some have described the academic publishing industry as a “racket”,

running on huge amounts of free labour while charging academic

institutions, and individual researchers, exorbitant fees to read papers

— and subsequently enjoying huge profit margins. How much labour do

publishers actually perform and can they really justify charging as much

as they do?

First, there’s a bit of a problem with referring to “publishers” as a

homogeneous group. It spans the giants of Elsevier, Taylor &

Francis, Wiley, Oxford University Press down to tiny university presses

that barely break even. It runs from for-profits through charities.

Publishers are many things.

Publishers perform, though, a variety of labour functions. There’s a

(pretty eked-out) list of 96 things publishers do on the (pretty

conservative)

Scholarly Kitchen blog.

However, I think that the labour function is mostly coordinating peer

review, platform maintenance, typesetting, copyediting, proofreading,

digital preservation, legal, accountancy, marketing (which is partly

dissemination and partly business-model based) and general business

overheads. List cultivation and actual editorial input might be placed

here for some humanities disciplines, but whether this is a needed

function or part of a business strategy remains hazy for me. Running OLH

is a full-time day job for me and my colleagues at the moment. I tend

to get up early and do my academic research reading and writing from

6:30 a.m. until 10 a.m. before then doing a full day of OLH work.

Publishers undoubtedly do things that we want and continue to

require. However, I do not see why (as above) this should legitimatize

extortionate levels of profit so that we can exclude others from reading

research. One recent criticism I saw, for instance, was

Daniel Allington comparing scholarly communications to a bar

(as the old jokes always go) in a Twitter reply and deriding OA

advocates for calling publishers “parasites.” Yet, Marx himself noted

that “capital is dead labour” describing it as “vampire-like.” To call

the profit-rates of mega companies a “racket” or “parasitical” is not to

deride the labour of their employees or even the desired labour

function. It is metaphorically to label such huge companies as a rentier

group who use a variety of canny business strategies to feed off

universities and achieve market dominance. Taylor & Francis, for

instance, wrote in

their annual shareholder report

that their revenue stream was “dominated by subscription assets with

high renewal rates, where customers generally pay us twelve months in

advance. This provides strong visibility on revenue and allows the

businesses to essentially fund themselves, with minimal external capital

required.” They believe that “it is a uniquely attractive mode.”

One problem I see with the “Gold” OA model (explanation provided here)

when author fees are involved, is that there’s an assumption that

everyone publishing is affiliated with an institution and has access to

institutional funding that can cover the cost. Many of those who want to

publish are early career academics who may not have institutional

support. To me it seems that the author-facing charges would inhibit

access to publishing for a lot of scholars. OLH has avoided this by

rejecting author fees; how does its funding model work? Would it be a

viable option beyond the humanities?

Yes, I agree with your assessment here. I think this comes from the

fact that many OA models have developed in the sciences, where much

research work requires (and has) external funding that can budget for

such charges. This is not universally the case, though. (And one

criticism of OA is the fact that it grew from the sciences and is being

applied elsewhere. I have long argued, though, that the benefits to the

humanities of open research work are as great as those for the sciences;

we just need a different implementation strategy.)

As above, OLH operates on a consortial funding model. Many libraries

pay a relatively small amount into our central budget. We then make work

openly available. There is precedent for this in

arXiv,

Knowledge Unlatched, and, to a lesser extent, the

SCOAP3

purchasing consortium. It’s not a totally new idea. But it is the first

time that a publisher has run its entire business model on this for

front-matter serials publication.

The key part of what we’re doing, though, is participating in schemes

to “flip” journals that were subscription to an open access model. In

some cases, this involves an editorial board leaving a publisher – as

did the editorial board of

Lingua – while in others it involves

us working with the university press to fund their journal; as with the

University of Wales Press. We currently have two other university

presses discussing flipping more substantial portions of their lists

through the OLH model.

Certainly, though, there is no reason why what we’ve done could not

be expanded beyond the disciplines in which we operate. However, we’d

need to grow more rapidly and have more initial capacity if we were to

run an Open Library of Science, for instance. Indeed, we’d need upfront

funder investment to expand our consortium size at a swifter rate and to

a higher level than we currently plan.

A lot of the discussion about “openness” has been about the

sciences; your area is the humanities (and that’s the topic of your

book). I have to apologise for not having read it yet — but what would

you say are the specific challenges for the humanities (and perhaps for

the social sciences as well) when it comes to open access scholarly

publishing? How might those compare to what’s going on in STEM areas?

There are several challenges that are more pronounced in the

humanities so I’ll just touch on a few here: the importance and

prominence of monographs; the inclusion of third-party copyrighted

material as an integral component of work (say in art history); and the

different funding climate.

Monographs are tricky. They cost a lot more, they often have trade

crossover, and they sometimes gain a broader audience by being available

for sale in print. Certainly, I personally do not want to read 80,000

words on a screen for cover-to-cover reading. But that doesn’t mean that

there isn’t merit in having books openly available; particularly as

these can cost $100 or so per copy. In any case, a task force has been

set up in the U.K. to plan a transition scheme to enable OA monographs

by the mid-2020s. I’ve also sketched out some

initial challenges in this space on my blog.

The third-party copyright matter is also a bit of sticking point.

Without such inclusions work is often severely impoverished. When

analysing images, if the image is not there, the evidence to back up the

point is not clear; this is also an access issue. Getting clearance for

images for unlimited online dissemination can be tough since galleries,

libraries, archives, and museums are often not accustomed (yet) to such

requests.

Finally, as above, the transition to OA in the humanities looks

harder, since it is unclear whence the funding for APCs will emerge.

Opponents of OA also argue that the journal costs in the humanities for

subscriptions are lower than in the sciences, implying that they think

the fuss isn’t worth it. Yet I have never worked at an institution that

has subscriptions to every journal that I need for my research work, on

the grounds of cost, so I’m not buying this.

None of this is to say that there aren’t specific challenges for the

humanities but I prefer to think of the opportunities. Imagine a world

where humanistic knowledge and inquiry – that is, research work about

culture and humans – was available freely to every human on the planet.

Is that not a goal worthy of overcoming a few hurdles?

What do you think are the most salient critiques of open access for academic publishing?

There are lots of very poor attacks on OA that I am tired of

defending but the ones that are most salient seem to me to be the

pragmatic critiques. How are we actually going to do this? How can we

achieve that universal library for anyone who is interested in reading,

without discriminating on their ability to pay? Usually, these critiques

don’t come with answers. They point out the dire economic circumstances

for the humanities, the difficulties of freeing subscription revenue

etc. These are useful when they provide models to warn us of the

challenges and dangers. But I am also interested in how we move from

theory to practice. My book on OA (itself open access from Cambridge

University Press) is designed as a theoretical basis on which the OLH or

others can operate. It’s not a sales pitch for the model it’s just that

I am not content with merely philosophising about the world; the point,

after all, is to change it.

So much about the academic profession is shifting; I know

this is always the case — and we are always acutely aware of our own

time, particularly when it comes to technology and its effects. Given

the nature of academic institutions, what changes to scholarly

publishing (as knowledge dissemination) do you think might unfold within

the span of your career?

This is the kind of question that can come back to haunt the

interviewee and I’m very wary of such futurology! It’s also worth noting

that things move at a

glacial pace within the academy.

However, things I see happening already include a desire for open

access among early career humanists. If at least some of them want it,

then it is likely to happen. Data sharing in various ways is also on the

up. I hope that we will see books available openly online for the good

of all. I also hope that text and data mining provisions through the

availability of semantically rich research articles can help us to more

accurately understand the scholarly web and its contents.

Lavina

Lavina