academic social networking

The Scholarly Communication Practices of Medical Sciences and Health Sciences users on Academia.edu: A guided research study

As some of you may know, I recently completed my coursework for my

MLIS degree (yay!) and am finally all set to graduate in October. What

many of you may not know is that I chose to finish my degree by

completing a guided research study

instead of traditional coursework. Over the last 8 months, I have had

the opportunity to explore one of my research interests: the scholarly

communication patterns of users on academic social networking sites.

The uptake of academic social networking sites is an interesting

phenomenon. These platforms allow scholars to list their papers in a CV

type fashion, to share their research, to name their research interests,

and to look for others with similar research interests to their own.

Members can even upload their manuscripts and preprints and ask for

feedback on works in progress- which invites comparison to the

traditional peer review process found in academia. In other words, these

sites are being used for informal scholarly communication. But how are

scholars using these sites? Are social networking norms present or do

these sites follow the scholarly status quo ? Are there disciplinary

differences with regards to who is using these sites? These are just a

few of the questions that I’ve encountered during my research.

Following is a brief overview of my study, some of my findings, and a few ideas for future research.

Many academics are active users of social media (Facebook, Twitter,

LinkedIn) and some even use these sites for professional networking. In

one study conducted by Procter et al. (2010), the authors found that 80%

of academics had a social media account, while 13% of scholars reported

using social media in novel forms of scholarly communication. For

example, a few studies have examined how Twitter allows scholars to

follow sessions and topics covered at academic conferences and the

relationship between sharing research on social media and citation

counts (Letierce, Passant, Breslin, Decker, 2010; Weller, Dornstädter,

Freimanis, Klein, & Perez, 2010; Weller & Puschmann, 2011).

However, while scholars can use traditional social networking

platforms to network with their peers, share research articles, and keep

up to date in their fields, there are some limitations that emerge when

these sites are used for academic purposes. A number of scholars have

expressed a perceived loss of personal privacy while using these

networks, while others have reported difficulties maintaining boundaries

between their personal and professional lives (Gruzd, 2012). As a

result, many academics have multiple social media accounts in order to

achieve a better work-life balance (Gruzd, 2012).

This is where academic social networking sites come into

play. Academic social networking sites, or social media sites designed

specifically for scholars, have emerged as one alternative to

traditional social networking services (Gruzd, 2012). Some examples of

popular academic social networking sites include Academia.edu, Mendeley,

and ResearchGate. After joining one of these sites, users are

encouraged to create a research profile, add contacts, search for

members with similar research interests, create and/or join groups, and

participate on discussion boards. Members can also consult a news feed

that updates them on the latest uploaded papers and comments from others

in their network (Oh & Jeng, 2011; Krause, 2012). A few academic

social networking sites, such as Mendeley and Zotero, also offer

bibliographic management tools to help scholars manage their documents

and citations (Jeng, He, & Jiang, 2015). Most academic social

networking sites, including Academia.edu and ResearchGate,

employ altmetrics that allow scholars to track their profile and

document views, total publications, total impact points, and downloads

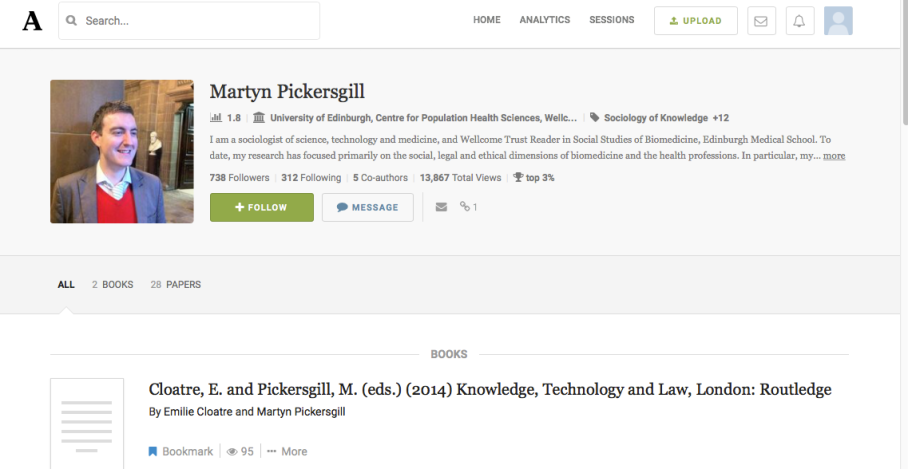

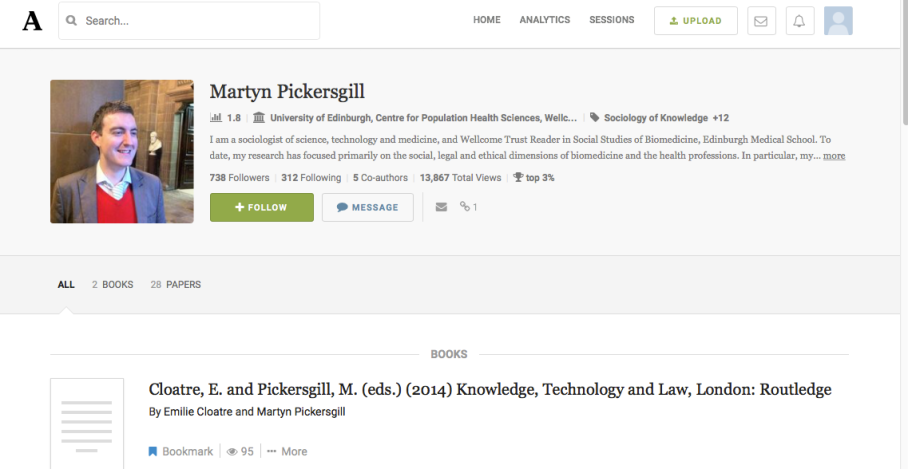

(See Figure 1).

How do these sites play a role in the scholarly communication process?

However, beyond allowing researchers the ability to track the

discussion and attention garnered by their work, academic social

networking sites are also formally playing a role in the scholarly

communication process. Scholarly communication can be defined as “the

system through which research and other scholarly writings are created,

evaluated for quality, disseminated to the scholarly community, and

preserved for future use” (ACRL, 2015). The introduction and subsequent

success of academic social networking sites, such as ResearchGate,

Academia.edu, and LinkedIn, have changed the way in which scholars

connect, collaborate, and disseminate their research (Greenhow, 2009;

Weintraub, 2012; Zaugg, West, Tateishi, & Randall, 2010). Many of

these more professionally marketed social media sites encourage members

to list their documents on their profiles and even give users the option

of uploading their manuscripts and preprints. Users of these sites are

then encouraged to share their research with their scholarly network or

with the broader (and often worldwide) academic community via

traditional social media sites (i.e. Twitter). Such examples suggest

that academic social networking sites are also being used as a venue for

scholarly communication.

But are scholars actually using academic social networking sites to

share their research and to network and collaborate with others? A study

by Jordan (2014) revealed that most scholars on academic social

networking sites view their profiles as an ‘online business card’ or

curriculum vitae, rather than as a site for active interaction with

others. However, participants did like the concept of using the site to

promote their research, particularly junior researchers (Jordan, 2014). A

more recent study conducted by Jeng, He, and Jiang (2015) found

contradictory results. The authors examined user participation on the

academic social networking site Mendeley. While the majority of

participants reported using the site for its research features, or as a

document or citation management tool, many members also used Mendeley to

manage their academic contacts and to expand their professional

networks. There is also evidence to suggest that researchers are using

academic social networking sites to find scholars with similar research

interests to their own and to keep up to date in their fields. Results

from a survey of physicists, linguists, and sociologists on

Academia.edu, for example, showed that these academics are using the

site to read articles posted by other researchers. Participants also

searched for members with similar research interests to their own

(Megwalu, 2015). These studies suggest that academic social networking

sites are platforms where both formal and informal scholarly

communication occur, creating a unique space to study existing and

emerging communication behaviours.

Who is using these sites?

Fortunately, several studies have tried to address this question by

examining the academic status of those who use academic social

networking sites. For example, a study by Jordan (2014) investigated the

impact of academic seniority on network structure on Academia.edu.

Results of the study indicated that a user’s number of connections and

position within the network was dependent on academic seniority. Senior

academics tended to have more connections and a more prominent position

within the network in comparison to junior researchers. Professors also

had a stronger tendency to only follow people who they knew personally

in real life and were less likely to try and make new connections on the

site. In other words, professors enjoyed a privileged position within

the network, even though they were not actively trying to network as

much as students.

However, it is possible that this advantage is not due to academic

seniority, but to a higher user group activity. In a study by Megwalu

(2015), students were more likely to register on Academia.edu, but

post-docs and faculty members had the highest number of logins over a

ten-month period, making them more frequent users than students. In

another study conducted by Thelwall and Kousha (2014), the authors

discovered that students tended to list more interests then faculty, but

that faculty listed more books and papers and were cited more often

than students. Also, senior researchers received substantially more

document views and profile views than junior researchers. This study

confirms previous research by Almousa (2011), where faculty were found

to be more active and uploaded more documents than any other group in

all three disciplines studied.

Why medical sciences and health sciences?

While many studies have examined disciplinary differences in the use

of academic social networking sites, very little research has examined

the scholarly communication practises of health and medical researchers

on these sites. In one study conducted by Oh and Jeng (2011), the

authors looked at participation in Mendeley groups by discipline.

Results of the study showed that Medicine was the third largest member

group and had a high level of group member participation. In another

more recent study by Mohammadi, Thelwall, Haustein, and Larivière

(2015), the authors found that non-academics (medical professionals)

read more clinical medicine articles on Mendeley than academics.

Thus, more research is needed in order to see whether scholars in

the health and medical field are using academic social networking sites

for scholarly communication. To address these gaps that persist in the

literature, this study sought to answer the following research questions

by focusing on faculty and graduate students in two disciplines –

Medical Sciences and Health Sciences – on Academia.edu:

practices of health and medical disciplines on Academia.edu. Results

indicate that there are large populations of Medical Sciences and Health

Sciences users on Academia.edu and that these scholars are using the

site to network and collaborate with others, to share their research,

and to keep up to date in their fields. In other words, researchers in

the health and medical field are using academic social networking sites

for scholarly communication. More research is needed, however, in order

to determine the extent to which the site mirrors existing academic

structures (i.e. the faculty – student advantage) and social networking

patterns (age, gender, etc.). Further studies should also examine why

these scholars register for an account on Academia.edu over (or in

addition to) other more specialized social networking tools available to

non-academics in the health and medical field (i.e. Sermo, Medscape,

MDLinx). Web-based applications for scholarly communication evolve

rapidly and disciplinary norms are constantly changing, as are the

communication preferences of scholars on these sites. More research is

needed in order to understand this ever-shifting landscape.

Almousa, O. (2011, December). Users’ classification and usage-pattern identification in academic social networks. In Applied Electrical Engineering and Computing Technologies (AEECT), 2011 IEEE Jordan Conference on (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

Greenhow, C. (2009). Social scholarship: Applying social networking technologies to research practices. Knowledge Quest, 37(4), 42.

Gruzd, A. (2012). Non-academic and academic social networking sites for online scholarly communities. Social media for academics: A practical guide, 21-37.

Jeng, W., He, D., & Jiang, J. (2015). User participation in an

academic social networking service: A survey of open group users on

Mendeley. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(5), 890-904.

Jordan, K. (2014). Academics and their online networks: Exploring the role of academic social networking sites. First Monday, 19(11).

Krause, J. (2012). Tracking reference with social media tools:

Organizing what you’ve read or want to read. In D. R. Neal (Ed.), Social media for academics: A practical guide (pp. 85-104). Oxford: Chandos Pub.

Letierce, J., Passant, A., Breslin, J., & Decker, S. (2010).

Understanding how Twitter is used to widely spread Scientific Messages.

In Proceedings of the WebSci10 Extending the Frontiers of Society Online.

Megwalu, A. (2015). Academic Social Networking: A Case Study on Users’ Information Behavior. In Current Issues in Libraries, Information Science and Related Fields (pp. 185-214). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Mohammadi, E., Thelwall, M., Haustein, S., & Larivière, V.

(2015). Who reads research articles? An altmetrics analysis of Mendeley

user categories. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(9), 1832-1846.

Oh, J. S., & Jeng, W. (2011, October). Groups in Academic Social

Networking Services–An Exploration of Their Potential as a Platform for

Multi-disciplinary Collaboration. In Privacy, Security, Risk and

Trust (PASSAT) and 2011 IEEE Third Inernational Conference on Social

Computing (SocialCom), 2011 IEEE Third International Conference on (pp. 545-548). IEEE.

Procter, R., Williams, R., Stewart, J., Poschen, M., Snee, H., Voss,

A., & Asgari-Targhi, M. (2010). Adoption and use of Web 2.0 in

scholarly communications. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 368(1926), 4039-4056.

Thelwall, M., & Kousha, K. (2014). Academia. edu: social network or academic network?. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(4), 721-731.

Weintraub, A. (2014). Social networks attempt to spark academic university collaborations (vol 30, pg 901, 2013). NATURE BIOTECHNOLOGY, 32(3), 212-212.

Weller, K., Dornstädter, R., Freimanis, R., Klein, R. N., &

Perez, M. (2010). Social software in academia: Three studies on users’

acceptance of Web 2.0 Services.

Weller, K., & Puschmann, C. (2011). Twitter for scientific

communication: How can citations/references be identified and measured?.

(pp. 1-4). In Proceedings of the ACM WebSci’11, June 14-17 2011, (pp. 1-4). Germany: Koblenz.

Zaugg, H., West, R. E., Tateishi, I., & Randall, D. L. (2011).

Mendeley: Creating communities of scholarly inquiry through research

collaboration. TechTrends, 55(1), 32-36.

MLIS degree (yay!) and am finally all set to graduate in October. What

many of you may not know is that I chose to finish my degree by

completing a guided research study

instead of traditional coursework. Over the last 8 months, I have had

the opportunity to explore one of my research interests: the scholarly

communication patterns of users on academic social networking sites.

The uptake of academic social networking sites is an interesting

phenomenon. These platforms allow scholars to list their papers in a CV

type fashion, to share their research, to name their research interests,

and to look for others with similar research interests to their own.

Members can even upload their manuscripts and preprints and ask for

feedback on works in progress- which invites comparison to the

traditional peer review process found in academia. In other words, these

sites are being used for informal scholarly communication. But how are

scholars using these sites? Are social networking norms present or do

these sites follow the scholarly status quo ? Are there disciplinary

differences with regards to who is using these sites? These are just a

few of the questions that I’ve encountered during my research.

Following is a brief overview of my study, some of my findings, and a few ideas for future research.

Overview:

Why academic social networking sites (i.e Academia.edu)?Many academics are active users of social media (Facebook, Twitter,

LinkedIn) and some even use these sites for professional networking. In

one study conducted by Procter et al. (2010), the authors found that 80%

of academics had a social media account, while 13% of scholars reported

using social media in novel forms of scholarly communication. For

example, a few studies have examined how Twitter allows scholars to

follow sessions and topics covered at academic conferences and the

relationship between sharing research on social media and citation

counts (Letierce, Passant, Breslin, Decker, 2010; Weller, Dornstädter,

Freimanis, Klein, & Perez, 2010; Weller & Puschmann, 2011).

However, while scholars can use traditional social networking

platforms to network with their peers, share research articles, and keep

up to date in their fields, there are some limitations that emerge when

these sites are used for academic purposes. A number of scholars have

expressed a perceived loss of personal privacy while using these

networks, while others have reported difficulties maintaining boundaries

between their personal and professional lives (Gruzd, 2012). As a

result, many academics have multiple social media accounts in order to

achieve a better work-life balance (Gruzd, 2012).

This is where academic social networking sites come into

play. Academic social networking sites, or social media sites designed

specifically for scholars, have emerged as one alternative to

traditional social networking services (Gruzd, 2012). Some examples of

popular academic social networking sites include Academia.edu, Mendeley,

and ResearchGate. After joining one of these sites, users are

encouraged to create a research profile, add contacts, search for

members with similar research interests, create and/or join groups, and

participate on discussion boards. Members can also consult a news feed

that updates them on the latest uploaded papers and comments from others

in their network (Oh & Jeng, 2011; Krause, 2012). A few academic

social networking sites, such as Mendeley and Zotero, also offer

bibliographic management tools to help scholars manage their documents

and citations (Jeng, He, & Jiang, 2015). Most academic social

networking sites, including Academia.edu and ResearchGate,

employ altmetrics that allow scholars to track their profile and

document views, total publications, total impact points, and downloads

(See Figure 1).

Figure 1. The profile page of a Health Sciences user on Academia.edu

How do these sites play a role in the scholarly communication process?

However, beyond allowing researchers the ability to track the

discussion and attention garnered by their work, academic social

networking sites are also formally playing a role in the scholarly

communication process. Scholarly communication can be defined as “the

system through which research and other scholarly writings are created,

evaluated for quality, disseminated to the scholarly community, and

preserved for future use” (ACRL, 2015). The introduction and subsequent

success of academic social networking sites, such as ResearchGate,

Academia.edu, and LinkedIn, have changed the way in which scholars

connect, collaborate, and disseminate their research (Greenhow, 2009;

Weintraub, 2012; Zaugg, West, Tateishi, & Randall, 2010). Many of

these more professionally marketed social media sites encourage members

to list their documents on their profiles and even give users the option

of uploading their manuscripts and preprints. Users of these sites are

then encouraged to share their research with their scholarly network or

with the broader (and often worldwide) academic community via

traditional social media sites (i.e. Twitter). Such examples suggest

that academic social networking sites are also being used as a venue for

scholarly communication.

But are scholars actually using academic social networking sites to

share their research and to network and collaborate with others? A study

by Jordan (2014) revealed that most scholars on academic social

networking sites view their profiles as an ‘online business card’ or

curriculum vitae, rather than as a site for active interaction with

others. However, participants did like the concept of using the site to

promote their research, particularly junior researchers (Jordan, 2014). A

more recent study conducted by Jeng, He, and Jiang (2015) found

contradictory results. The authors examined user participation on the

academic social networking site Mendeley. While the majority of

participants reported using the site for its research features, or as a

document or citation management tool, many members also used Mendeley to

manage their academic contacts and to expand their professional

networks. There is also evidence to suggest that researchers are using

academic social networking sites to find scholars with similar research

interests to their own and to keep up to date in their fields. Results

from a survey of physicists, linguists, and sociologists on

Academia.edu, for example, showed that these academics are using the

site to read articles posted by other researchers. Participants also

searched for members with similar research interests to their own

(Megwalu, 2015). These studies suggest that academic social networking

sites are platforms where both formal and informal scholarly

communication occur, creating a unique space to study existing and

emerging communication behaviours.

Who is using these sites?

Fortunately, several studies have tried to address this question by

examining the academic status of those who use academic social

networking sites. For example, a study by Jordan (2014) investigated the

impact of academic seniority on network structure on Academia.edu.

Results of the study indicated that a user’s number of connections and

position within the network was dependent on academic seniority. Senior

academics tended to have more connections and a more prominent position

within the network in comparison to junior researchers. Professors also

had a stronger tendency to only follow people who they knew personally

in real life and were less likely to try and make new connections on the

site. In other words, professors enjoyed a privileged position within

the network, even though they were not actively trying to network as

much as students.

However, it is possible that this advantage is not due to academic

seniority, but to a higher user group activity. In a study by Megwalu

(2015), students were more likely to register on Academia.edu, but

post-docs and faculty members had the highest number of logins over a

ten-month period, making them more frequent users than students. In

another study conducted by Thelwall and Kousha (2014), the authors

discovered that students tended to list more interests then faculty, but

that faculty listed more books and papers and were cited more often

than students. Also, senior researchers received substantially more

document views and profile views than junior researchers. This study

confirms previous research by Almousa (2011), where faculty were found

to be more active and uploaded more documents than any other group in

all three disciplines studied.

Why medical sciences and health sciences?

While many studies have examined disciplinary differences in the use

of academic social networking sites, very little research has examined

the scholarly communication practises of health and medical researchers

on these sites. In one study conducted by Oh and Jeng (2011), the

authors looked at participation in Mendeley groups by discipline.

Results of the study showed that Medicine was the third largest member

group and had a high level of group member participation. In another

more recent study by Mohammadi, Thelwall, Haustein, and Larivière

(2015), the authors found that non-academics (medical professionals)

read more clinical medicine articles on Mendeley than academics.

Thus, more research is needed in order to see whether scholars in

the health and medical field are using academic social networking sites

for scholarly communication. To address these gaps that persist in the

literature, this study sought to answer the following research questions

by focusing on faculty and graduate students in two disciplines –

Medical Sciences and Health Sciences – on Academia.edu:

R1: Is there a correlation between academic seniority and user activity (# of listed documents) on Academia.edu?

R2: Is there a

relationship between academic seniority and altmetrics score (# of

profile views, # of followers) on Academia.edu?

relationship between academic seniority and altmetrics score (# of

profile views, # of followers) on Academia.edu?

R3: Are there disciplinary differences in use between Medical Sciences and Health Sciences?

Summary of Findings:

Overall, faculty members

were the most active user group on Academia.edu. In both Medical

Sciences and Health Sciences, more faculty members than graduate

students registered for an account on Academia.edu (See Figure 2 &

Figure 3 below). Faculty members also added significantly more documents

to their profiles than did graduate students in both Medical Sciences

and Health Sciences.

were the most active user group on Academia.edu. In both Medical

Sciences and Health Sciences, more faculty members than graduate

students registered for an account on Academia.edu (See Figure 2 &

Figure 3 below). Faculty members also added significantly more documents

to their profiles than did graduate students in both Medical Sciences

and Health Sciences.

However, despite being

more active on the site, faculty members did not necessarily enjoy a

more privileged position within the network. While Health Sciences

faculty had significantly more profile views and followers than graduate

students, Medical Sciences graduate students had more profile views and

followers than faculty members. Also, the number of documents listed on

a user’s profile page had little bearing on the number of profile views

and number of followers that they received.

more active on the site, faculty members did not necessarily enjoy a

more privileged position within the network. While Health Sciences

faculty had significantly more profile views and followers than graduate

students, Medical Sciences graduate students had more profile views and

followers than faculty members. Also, the number of documents listed on

a user’s profile page had little bearing on the number of profile views

and number of followers that they received.

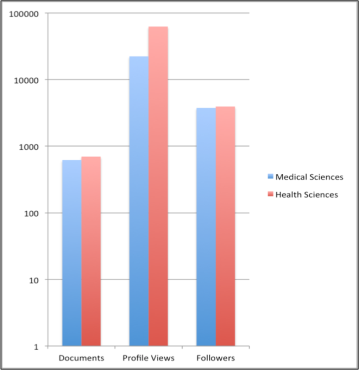

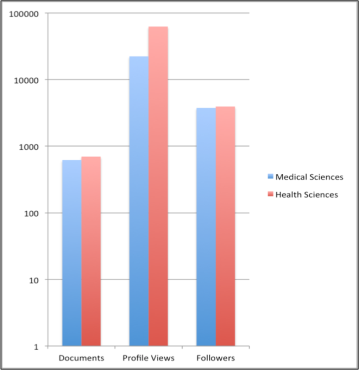

In regards to disciplinary

differences between Medical Sciences and Health Sciences, Health

Sciences was the more active user discipline. Health Sciences faculty

members and graduate students uploaded more documents to their profiles

(699 : 621 total documents respectively) and received more profile views

and followers than their Medical Sciences counterparts. The most

notable difference between the two disciplines is evident when comparing

the number of profile views received, as members from the Health

Sciences community had nearly three times as many profile views as those

in Medical Sciences (See Figure 4).

differences between Medical Sciences and Health Sciences, Health

Sciences was the more active user discipline. Health Sciences faculty

members and graduate students uploaded more documents to their profiles

(699 : 621 total documents respectively) and received more profile views

and followers than their Medical Sciences counterparts. The most

notable difference between the two disciplines is evident when comparing

the number of profile views received, as members from the Health

Sciences community had nearly three times as many profile views as those

in Medical Sciences (See Figure 4).

Figure 4. Total number of documents, profile views, and followers for Medical Sciences and Health Sciences on Academia.edu

Conclusions:

This study has provided insight into the scholarly communicationpractices of health and medical disciplines on Academia.edu. Results

indicate that there are large populations of Medical Sciences and Health

Sciences users on Academia.edu and that these scholars are using the

site to network and collaborate with others, to share their research,

and to keep up to date in their fields. In other words, researchers in

the health and medical field are using academic social networking sites

for scholarly communication. More research is needed, however, in order

to determine the extent to which the site mirrors existing academic

structures (i.e. the faculty – student advantage) and social networking

patterns (age, gender, etc.). Further studies should also examine why

these scholars register for an account on Academia.edu over (or in

addition to) other more specialized social networking tools available to

non-academics in the health and medical field (i.e. Sermo, Medscape,

MDLinx). Web-based applications for scholarly communication evolve

rapidly and disciplinary norms are constantly changing, as are the

communication preferences of scholars on these sites. More research is

needed in order to understand this ever-shifting landscape.

References:

ACRL Scholarly Communications Committee. (2003). Principles and Strategies for the Reform of Scholarly Communication.Almousa, O. (2011, December). Users’ classification and usage-pattern identification in academic social networks. In Applied Electrical Engineering and Computing Technologies (AEECT), 2011 IEEE Jordan Conference on (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

Greenhow, C. (2009). Social scholarship: Applying social networking technologies to research practices. Knowledge Quest, 37(4), 42.

Gruzd, A. (2012). Non-academic and academic social networking sites for online scholarly communities. Social media for academics: A practical guide, 21-37.

Jeng, W., He, D., & Jiang, J. (2015). User participation in an

academic social networking service: A survey of open group users on

Mendeley. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(5), 890-904.

Jordan, K. (2014). Academics and their online networks: Exploring the role of academic social networking sites. First Monday, 19(11).

Krause, J. (2012). Tracking reference with social media tools:

Organizing what you’ve read or want to read. In D. R. Neal (Ed.), Social media for academics: A practical guide (pp. 85-104). Oxford: Chandos Pub.

Letierce, J., Passant, A., Breslin, J., & Decker, S. (2010).

Understanding how Twitter is used to widely spread Scientific Messages.

In Proceedings of the WebSci10 Extending the Frontiers of Society Online.

Megwalu, A. (2015). Academic Social Networking: A Case Study on Users’ Information Behavior. In Current Issues in Libraries, Information Science and Related Fields (pp. 185-214). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Mohammadi, E., Thelwall, M., Haustein, S., & Larivière, V.

(2015). Who reads research articles? An altmetrics analysis of Mendeley

user categories. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(9), 1832-1846.

Oh, J. S., & Jeng, W. (2011, October). Groups in Academic Social

Networking Services–An Exploration of Their Potential as a Platform for

Multi-disciplinary Collaboration. In Privacy, Security, Risk and

Trust (PASSAT) and 2011 IEEE Third Inernational Conference on Social

Computing (SocialCom), 2011 IEEE Third International Conference on (pp. 545-548). IEEE.

Procter, R., Williams, R., Stewart, J., Poschen, M., Snee, H., Voss,

A., & Asgari-Targhi, M. (2010). Adoption and use of Web 2.0 in

scholarly communications. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 368(1926), 4039-4056.

Thelwall, M., & Kousha, K. (2014). Academia. edu: social network or academic network?. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(4), 721-731.

Weintraub, A. (2014). Social networks attempt to spark academic university collaborations (vol 30, pg 901, 2013). NATURE BIOTECHNOLOGY, 32(3), 212-212.

Weller, K., Dornstädter, R., Freimanis, R., Klein, R. N., &

Perez, M. (2010). Social software in academia: Three studies on users’

acceptance of Web 2.0 Services.

Weller, K., & Puschmann, C. (2011). Twitter for scientific

communication: How can citations/references be identified and measured?.

(pp. 1-4). In Proceedings of the ACM WebSci’11, June 14-17 2011, (pp. 1-4). Germany: Koblenz.

Zaugg, H., West, R. E., Tateishi, I., & Randall, D. L. (2011).

Mendeley: Creating communities of scholarly inquiry through research

collaboration. TechTrends, 55(1), 32-36.

Tagged Academia.edu, academic social networking, health sciences, information behavior, medical sciences, scholarly communication

academic social networking | liddylib