Source: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11456109.v1

In order to improve the quality of systematic researches, various tools have been developed by well-known scientific institutes sporadically. Dr. Nader Ale Ebrahim has collected these sporadic tools under one roof in a collection named “Research Tool Box”. The toolbox contains over 720 tools so far, classified in 4 main categories: Literature-review, Writing a paper, Targeting suitable journals, as well as Enhancing visibility and impact factor.

Source: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11456109.v1

Source: https://blogs.unimelb.edu.au/23researchthings/2020/08/05/thing-15-text-mining/

Are you a researcher working on text-based projects? Ever tried to make sense of all those social media posts, or analyse a long and complex literary text? Wrangling large volumes of text can be a challenge, so in this post Kim Doyle introduces text mining concepts and tools to make this task easier.

Text mining (also known as text data mining or text analytics) is a broad name for a number of processes and practices that gather and examine large collections of written resources to discover new information or answer a specific research question. Typically, this analysis begins with information retrieval, which involves the identification of relevant textual materials in a file, database, on the Web, or in some other digitised format. Automated analysis is performed by specialised computer software to structure text for analysis, derive patterns from the resulting data, and interpret the output. One of the most common and important methodologies for processing text is Natural Language Processing (NLP). It can be used to extract precise information, analyse meaning, classify text, find relevant entities and relationships in language, and more.

Text data can be gathered and processed from a wide variety of sources, including documents, books, digital archives, library catalogues, websites, and social media streams like Facebook and Twitter, or any combination of these. The format these sources are stored in will determine data acquisition techniques. In many cases you may already have your data, or be able to simply download text files from a repository. However, if you want to harvest data from the Web, you may need to connect to an Application Programming Interface (API) or perform Web scraping, especially if you are interested in social media data. This may require programming skills, depending on the scale and scope of the data collection.

The size and structure of the data will determine the most appropriate textual analysis techniques. Small datasets might not be appropriate for computational analysis. Some statistical techniques, such as topic modelling, require large amounts of data to produce meaningful results. Beyond the size of the data, the methods of analysis will be determined by your research interests. It is important to make sure methods are appropriate both for the size and structure of the data, but also that they are able to answer your research questions.

Some examples of computational techniques include:

Working with data-driven techniques, software packages, and programming tools can be a steep learning curve. Below are a few tools to get you started. The Web-based tool Voyant is a good introduction to text mining and can address many research questions. On the other end of the scale, programming tools such as Python and R are customisable, but can be intimidating at first glance. Below are introductory texts for R and Python written specifically for simplified text mining. Orange Text Mining uses a graphical user interface to create workflows to analyse text. You will find a range of introductory videos on its website.

| Voyant Tools | Orange Text Mining | Text Mining with R | Textblob: Python Library | |

| Cost | Free | Free | Free | Free |

| Licence | Closed source | GPL / GNU General Public License | Open source | Open source |

| Usability | Easy | Easy | Intermediate | Intermediate |

| Tool type | Web application | Desktop application | Programming language | Programming language |

| Import formats | TXT, CSV, HTML, XML, PDF, RTF, URL | TXT, CSV, HTML, XML, URL | Most formats | Most formats |

| Export formats | TXT, CSV, XML | CSV, TAB | Most formats | Most formats |

The data, tools and techniques you use should be documented in your Data Management Plan. This will help you conceive your data project, keep good documentation, and maintain your data for future research in accordance with the University’s data retention policy. As always, when using these analytical tools to analyse your data (especially those tools only available online), you must carefully consider the potential privacy risks, and what measures will be needed to mitigate those risks (e.g. making personal or sensitive data anonymous). For privacy, ethics and security issues, it is strongly recommended to contact experts from the University’s Office of Research Ethics and Integrity prior to using any of these online tools. In some cases ethics approval should be sought before data collection (Facebook data, for example) and this should be factored into project timelines.

The depth of this topic means only a small fraction of available text mining tools and processes are covered here. There are certainly other options that might be worth considering depending on your specific requirements and research questions. If you are keen to delve deeper and learn some coding, Natural Language Processing with Python is a good introduction to concepts in NLP and writing programs, regardless of previous programming experience.

If text mining is something you’re considering in your research, there are a couple of places within the University that can help:

Kim Doyle is a Research Data Specialist at the Melbourne Data Analytics Platform (MDAP) and a PhD in Media and Communications at the University of Melbourne. Previously, she taught natural language processing and data mining to researchers at the University of Melbourne’s Research Computing Services for a number of years. Her research interests include political communication, social media, and computational social science.

Want more from 23 Research Things? Sign up to our mailing list to never miss a post.

Source: https://blogs.unimelb.edu.au/23researchthings/2020/08/05/thing-16-data-visualisation/

Data visualisations can be a powerful way of synthesising your research and representing it in a way that’s understandable. Visualisations may take the form of charts or graphs, diagrams, images, animations, or infographics. They can be effective for communicating complex research, even to a non-expert audience. In this post, Gene Melzack introduces data visualisation as a way to make your research more accessible.

Data visualisation is closely tied to data analysis. You may want to perform some preliminary visualisations at the start of your analysis, as a way of getting to know the data and deciding what analysis methods to use (also known as ‘exploratory data analysis’). Research workflows may involve receiving updates to data or refining your analysis, which means you’ll need to update your visualisation in turn. If you can do all this with a single tool that handles both analysis and visualisation in one, it will streamline your workflow. Consider data visualisation capabilities when selecting a data analysis tool, as it could save you time and hassle later – even if it means initially choosing a tool with a steeper learning curve.

Before you dive in and choose a visualisation tool, you’ll need to consider the following points:

Is the visualisation a ‘quick and dirty’ one just for you, or is it for communicating your research to peers in the scholarly community, or to the public? This may influence whether you choose a simple or more complex visualisation.

Different types of visualisation suit different types of data. With so many options available, choosing the right visualisation style can seem overwhelming. For example, do you want to go with a network diagram or a bubble map? Or maybe a boxplot, or a cluster analysis?

The Data Visualisation Catalogue allows you to explore not only style, but also specific functions. Other great sites for inspiration are the Data Viz Project and From Data to Viz. Just ensure you choose a visualisation that communicates the message of your data effectively.

Is the visualisation for a conference presentation, journal article, or an interactive web visualisation? This will affect how the visualisation is displayed: in print or online, static or active, in colour or grayscale.

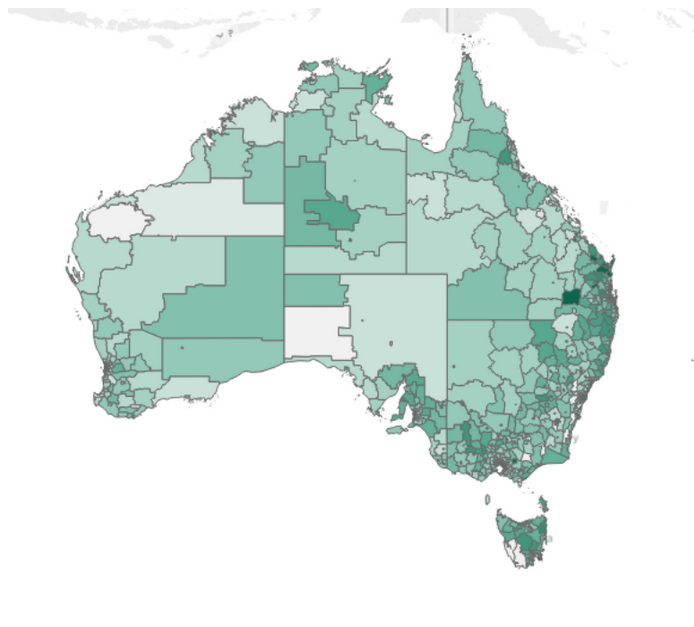

For an example of data visualisation in practice, click on the image below to explore an interactive map of Census data:

We’ve already established that, in most cases, the best approach is to visualise your data with the same tool you use for your data analysis. For example, if you analyse your data with MATLAB, consider using the inbuilt graphics functions for visualisation. Or if you use NVivo for data analysis, explore its visualisation options for Windows and Mac.

If you use scripting languages such as R or Python for data analysis, then there are a variety of packages or libraries you could choose. Here are some that come recommended by researchers who specialise in data analysis and visualisation:

The University of Melbourne’s Statistical Consulting Centre provide advice on visualisation good practice. Have a look at these five principles of good graphs, and find out why you shouldn’t use pie-charts.

Do you want to develop your visualisation skills? Access online trainings, self-paced tutorials, and e-learning videos with the Research Computing Services’ Digital Research Skills Support Pack. Or check out the Researcher@Library session on ‘How to Create Research Impact with Data Visualisation and Infographics’.

Gene Melzack is a Data Steward with the Digital Stewardship (Research) team. He works closely with the Research Data Specialists from the Melbourne Data Analytics Platform (MDAP), who provided expert data analysis and visualisation advice in the writing of this post.

Want more from 23 Research Things? Sign up to our mailing list to never miss a post.

Image available from https://plos.figshare.com/articles/A_Portrait_of_the_Transcriptome_of_the_Neglected_Trematode_em_Fasciola_gigantica_em_Biological_and_Biotechnological_Implications/139122 under a CC BY 4.0 license (created using iPath)

Source: https://blogs.unimelb.edu.au/23researchthings/2020/07/22/thing-12-research-engagement-and-impact/

In recent years there has been shift away from ‘traditional’ impact metrics (such as citation counts), in favour of an increased focus on identifying and assessing the real-world impact of research. This is often referred to as the ‘impact agenda’. In this post Kristijan Causovski, Justin Shearer, and Joann Cattlin investigate different types of impact, and how integrate them to into your research workflows.

The Australian Research Council (ARC) defines research impact as ‘the contribution that research makes to the economy, society, environment or culture, beyond the contribution to academic research’. While the nature of impact varies across disciplines and research methodologies, there are a number of broad categories through which to achieve impact:

In Australia, research impact has become a requirement of some funding bodies. The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and Medical Research Future Fund grants are introducing requirements for research translation and impact plans, while ARC grant applications now require a national interest statement. The ARC also assesses universities periodically through the Engagement and Impact assessment exercise, and engagement is part of the mission of many universities (e.g. Advancing Melbourne 2030). Researchers should consider how their research project or program can inform, benefit or provide value beyond academia and address this in their project plan.

A good, healthy stakeholder relationship is one of the most effective ways of creating impact. You can achieve this by planning engagement activities as part of a research project involving those who could be potentially affected by, use, or be interested in, the research outcomes. Engagement can take the form of:

In the research planning stage, it is a good idea to do a stakeholder analysis in order to map out the individuals or organisations with a potential interest in your research. Useful resources to help get you started include the Knowledge Translation Planning Primer and the UK’s National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement.

It is important to build evaluation mechanisms into your engagement activities so you can determine whether you are having an impact, and what the impact is. Evaluation can involve surveys, interviews, data collected from website hits and social media activity (altmetrics), emails and communications from stakeholders, as well as academic citations. Creating a plan for evaluation means that you are well prepared to collect and analyse this information, and you can adapt your approach as you conduct the research.

Various statistical methods are used to analyse authors, publications, and topics, often to measure their impact within a portfolio or subject area. Evaluation of research impact and engagement should be a balanced judgement, comprising an interpretation by peers in conjunction with research metrics, rather than a predominant or exclusive reliance on the latter. The metrics below are commonly used examples to provide supporting evidence for grant or promotion applications:

It is important to note that not all indicators are suitable for all disciplines. Differences in scholarly disciplines and individuals’ career pathways need to be factored into assessment. For example, the aforementioned h-index is well known to disadvantage early-career researchers (as the h-index can only grow over time), those with non-traditional career pathways, or those in low-citation count disciplines. Similarly, the journal impact factor is often used as an ersatz article-level metric – a purpose for which it is not intended. The best practice approach is to use a variety of indicators and only use them as part of an evaluation discussion to inform the conversation. No indicators are perfect.

In recognition of the challenges presented by the impact evaluation landscape, the University of Melbourne is a signatory to the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) – an initiative created with the aim of improving the ways in which the outputs of scholarly research are evaluated.

Kristijan Causovski is Digital Preservation Coordinator and Liaison Librarian, Business and Economics, Scholarly Services, at the University of Melbourne.

Justin Shearer is Associate Director, Research Information and Engagement, Scholarly Services, at the University of Melbourne.

Joann Cattlin is Manager, Research Engagement & Impact, Melbourne Law School.

Want more from 23 Research Things? Sign up to our mailing list to never miss a post.

Image: Arek Socha from Pixabay

Categories

Posted by

Source: https://blogs.unimelb.edu.au/23researchthings/2020/07/22/thing-11-managing-your-online-visibility/

Taking some time to manage your online presence as a researcher can make you more visible to the people who need or want to know about you. How would a recruiter, principle investigator, journalist or conference organiser know how to find you? Having a plan to manage your online visibility is a good idea, so in this post Christina Ward and Dr Trent Hennessey give you some tips to avoid this task becoming overwhelming.

If you aren’t googling yourself, someone else certainly is. To find out if you’re discoverable online – and in fact, what a search about you would uncover – you can replicate someone else’s experience by searching from a private browser. This will ensure your results aren’t skewed by your online history or signed in accounts. Try using more than one search engine, as results and rankings may be different. You might find you have a ‘digital doppelgänger’, that is, someone with the same, or similar, name. This doppelgänger may obscure your work, or your search may uncover some past online activity that you no longer want to highlight. Understanding your digital footprint can help you prioritise what to clean up and how to distinguish yourself when setting up your own profiles: for example, you may wish to use a variant of your name, like including your middle initial.

Recognising there are diverse research cultures and communities, it can be particularly useful to search for some of your peers, or researchers whose paths you would like to follow. What kind of web presence do they have? Which platforms are commonly used by researchers in your field? These quick searches will give you a good idea of the best channels and platforms for your discipline. It will also allow you to be more targeted with building and managing your visibility.

Now you know what the state of your online visibility is, let’s have a look at how to actively manage and promote yourself.

Researcher profiles are publicly accessible pages that give details of your scholarly achievements, including publications, grants, affiliations, and qualifications. They can provide current contact details, or links to portfolios or social media, making it easy to reach you even if you’ve moved institutions or changed your name.

Some platforms, such as Google Scholar or Scopus, may auto-generate a page for you based on the information held in their database. You’re not required to manage these pages, but if you choose to claim them, you can clean up the results by removing duplications or errors, so that the information is accurate.

For the most part, you can choose which platforms you engage with. However, all University of Melbourne research students and academic staff are required to have an ORCID (Open Researcher and Contributor ID). Your ORCID is a 16-digit number which is unique to you and connects with the University’s publications management system, Minerva Elements (a unimelb log-in is required to access Minerva Elements).

Many profiles will automatically update with your latest articles. They will also allow you to track citations that your research outputs have received.

The Researcher Profiles, Identifiers and Networks Library Guide will give you an overview of commonly-used profiles and their key features, as well as guidance on setting them up. Before making a choice, consider the following:

Keeping your profiles current signals to the world that you’re still an active part of your research community, making you a more attractive option to contact, for example if your topic is in the news and someone wants a comment or interview.

Remember to update your profile when you:

Managing your visibility requires ongoing work, and taking time at the outset to plan your approach will help you get the balance right. Consider which profile/s will be truly beneficial to you, then focus on keeping these up to date. This will be much more effective than setting up multiple profiles, but not maintaining any of them.

Christina Ward is a Liaison Librarian in the Law Library.

Dr Trent Hennessey is Program Manager of Environments and Experience in Scholarly Services. Trent is a strong advocate for lifelong learning, literacies, and libraries, understanding their transformative power to improve lives and develop knowledge societies globally.

Want more from 23 Research Things? Sign up to our mailing list to never miss a post.

Image: Lucas Wendt from Pixabay

Social

media can be a powerful tool for networking and raising your research

profile. Its conversational style fosters open, informal professional

connections and enables engagement with broader communities of interest. In this post, Andrea Hurt and Lisa O’Sullivan introduce the ‘big three’ social media platforms: Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

The way that researchers use social media is constantly evolving. These channels provide platforms to help build a public presence for you and your work. They can also help combat the sense of isolation some research students feel. Many research organisations also have own social media accounts, which often aim to present a more personal side to a corporate face. Whether it’s your own social media account or an institution, the primary function is to build relationships.

Firstly, consider why you are interested in social media and who you hope to engage with. Are you focussed on raising your own profile or creating a community? Do you hope to connect with others within your subject area, build more interdisciplinary connections, or share tips about the research process? Understanding your “target audience” will help you decide which platform(s) to use and when, how, and what you post.

With its 280–character limit, Twitter is a great platform to use to hone your skills in describing your interests in a succinct and engaging way. It’s probably the best social media platform for generating conversations and keeping up-to-date with what’s happening in your discipline or interest area.

Your academic status is not important on Twitter; you can use it to follow researchers or share and publicise your own work. You’ll also find many institutions using Twitter as a key promotional tool for their work. Perhaps most powerfully, you can use it to connect with other researchers and build a community.

Get tweeting!

Tweeting only when you have something to say, creating a consistent presence, and responding to others on the platform can all help you build your presence. Start by following people and organisations in your field and have a look at who they’re following as well. Using videos, well-known hashtags, and live tweeting events of interest can also be useful ways to get your content noticed.

Twitter allows threads to link longer stories together; but remember that each tweet can also be shared by itself, so make sure your tweets make sense in isolation. Remember that you will be tweeting to a global audience and be aware of cultural and linguistic differences.

Twitter Analytics can help you see the impact and reach your tweets are having, as well as information about your followers.

What others have tried

Some examples from the UniMelb community demonstrate the kind of identities you’ll find on Twitter that straddle the professional and personal in different ways:

Facebook is the most popular social media platform in Australia, with 16,000,000 monthly active Australian users (May 2020). Its popularity, ease of sharing information, and ability to create a space for conversation means it’s a channel for engagement and interaction. Don’t assume that the general public won’t be interested in accessing your research and sharing your interests! A surprising number of people love to hear about the nitty gritty of doing all kinds of research. Rather than boosting your personal profile, consider Facebook for creating audiences in two key ways:

Facebook features

What others have tried

Originally designed as a photo sharing platform, Instagram is now the third most popular social media channel, with 9,000,000 monthly active Australian users (May 2020). Instagram also allows for video sharing in your feed, via Instagram Stories, and through the new IGTV app.

Images lend themselves to storytelling, drawing the viewer into the work you do. Some accounts focus solely on research or a specific subject, while others blend the personal and professional. The visual diary aspect of Instagram allows followers to see all elements (work, study, social, family) of your life. And remember that humour can be a great way to get people to engage with your account.

Insta insights

What others have tried

Be realistic about what you want from being on social media, and the time you have available to build and maintain a consistent presence.

Decide on the boundaries of your social media presence: some people are comfortable posting professional and personal news from the same account, while others prefer to keep them strictly separate. You may have accounts representing you, your research, or your institutions’ work; in each case, the content you post may have a different tone and focus.

Be aware of etiquette around tagging others and posting information or images that might infringe on others’ privacy. Also be conscious of your personal liability for any material you post or share.

While social media posts can feel ephemeral, remember that once something is on the internet it can be difficult to erase. Many recruiters now openly search candidates’ social media accounts, so be thoughtful about what you post, especially on a platform like Twitter where posts can easily be shared and taken out of the context you intended.

Andrea Hurt is focussed on outreach and the user experience. People and spaces are her priority as the Senior Librarian, Library Services and Spaces in the Baillieu Library. With over 30 years’ experience, she has grown up in academic libraries. Andy is a lover of social media, digital communication, and spends a lot of time on Instagram. She is also the Library Social Media Coordinator. Andy is currently studying a Master of Communication with a specialisation in Digital Media.

Lisa O’Sullivan trained as a historian and has worked in archives, museums and libraries, particularly those relating to the cultural history of medicine and the natural sciences. In her current role she focuses on engagement and outreach for the Archives and Special collections of the University. She lurks on Twitter for most of her personal and professional news.

Want more from 23 Research Things? Sign up to our mailing list to never miss a post.

Image: Photo by Tracy Le Blanc from Pexels