Source: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2019/07/09/using-linkedin-for-social-research

Using LinkedIn for Social Research

Different social media platforms allow

different levels of access to the data they hold for academic research.

In this cross-post Daniela Duca explores some of the

ways in which LinkedIn has been used by social scientists and provides a

list resources for researchers looking to work with LinkedIn data.

Back in 2012, when LinkedIn was close to the 200 million users mark,

a young but very computational (and quite resourceful) assistant

professor, hustled through his contacts and somehow managed to get

access to the trove of LinkedIn data. Prasanna Tambe—at

the NYU Stern School of Business at the time—was not the first to use

the information on LinkedIn for research, but definitely the first to

use LinkedIn data to this scale. Tambe mined the skills and roles of all 175 million users

at the time, though he probably ended up working with a smaller sample,

to understand how the rapid evolution of skills and know-how in the

technology sector is impacting investments in new IT innovations.

Today, researchers are using LinkedIn data in a variety of ways: to find and recruit participants for research and experiments (Using Facebook and LinkedIn to Recruit Nurses for an Online Survey), to analyze how the features of this network affect people’s behavior and identity or how data is used for hiring and recruiting purposes, or most often to enrich other data sources with publicly available information from selected LinkedIn profiles (Examining the Career Trajectories of Nonprofit Executive Leaders, The

Tech Industry Meets Presidential Politics: Explaining the Democratic

Party’s Technological Advantage in Electoral Campaigning).Most of

these uses involve manual lookups and graduate students spending days to

sift through the site, copy pasting the information into a spreadsheet.

A LinkedIn API

is available for larger scale datasets, but there are limitations—such

as no more than 100k lifetime users, no storing of content, and it

cannot be used for research purposes. If you had a large enough network,

you could also download your network’s data

and work with that csv output. Essentially, you need some computational

skills to collect and use the LinkedIn data, and you would still be

limited in the type of research you could do. Gian Marco Campagnolo, a Turing Fellow and lecturer at the University of Edinburgh used some LinkedIn data for his team’s research into the career evolution of IT professionals, but they still needed to get a list of names from another database.

Economic Graph

With over 630 million users with 35

thousand skills, 30 million companies and 20 million advertised jobs,

researchers could explore an extensive set for labor market research.

LinkedIn acknowledged the power in this data and decided to make use of

it, while still protecting their members’ privacy. They launched a

project called the ‘economic graph’ to map out the world’s economy.

Aware of the benefits of working with researchers (remember Tambe),

LinkedIn opened up their data to the academic community, but in a

cautious way through the Economic Graph Challenge and later the Research Program.

After more than 200 applications, in 2017, LinkedIn selected 11 teams

to work with for a year. The second round of applications closed in

December 2018.The Economic Graph Research Program enabled researchers

like Laura Gee, from Tufts University, and Jessica Jeffers

from the University of Chicago, to use LinkedIn data and explore

questions around the attractiveness of job postings for men vs women, or

the impact of non-compete agreements and whether they hurt businesses.

An intriguing research project coming from Indiana University

(that LinkedIn is still working with) designed an algorithm to identify

“fine-grained geo-industrial clusters called “microindustries” (e.g.,

electric vehicle manufacturers in northern California, or Milanese

fashion houses) based on workers’ firm-to-firm transitions,” something

that could be quite useful for policy-makers.

The LinkedIn Economic Graph team continues to work with the data independently of academics, forming partnerships with organisations such as The World Bank Group.

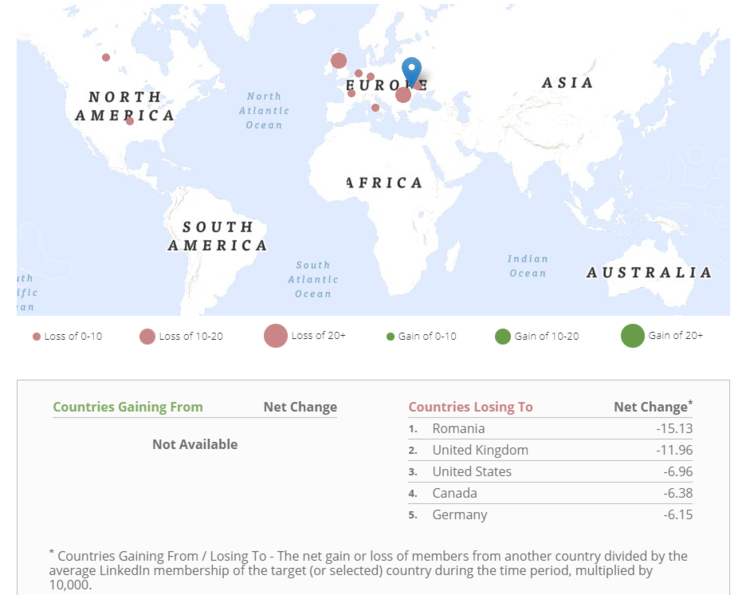

I was recently looking at the data made available (to the public

through this collaboration) to explore the migration patterns of highly

trained people from my home country. I was surprised to find that UK is

now #2 after Romania. As the website states, in this first Digital Data for Development

collaboration, the two organizations opened up an anonymized and

aggregated dataset on “100+ countries with at least 100,000 LinkedIn

members each, distributed across 148 industries and 50,000 skills

categories”.

Even more interestingly, the LinkedIn

Economic Graph is supplementing and reporting on major labor market

statistics with their monthly and quarterly workforce reports for

countries like the US, UK and India. In the UK the report is timed with

the trends reported by the ONS, and in the UK these reports go into more

detail than any other administrative dataset. Browsing their site, you

can find fascinating analysis into different population groups, like women breaking the glass ceiling faster but in smaller numbers.While

the effort that the LinkedIn group is making is laudable: the data they

are sharing at the macro level is helping governments and policy makers

across the world, and they are opening it up to a small group of

academics; there is still a gap that is quite hard to fill. The data

remains proprietary and there is little incentive and too much risk in

spending time reviewing every single application from academics around

the world that have a genuine interest in working with data that

contains enormous amounts of detail about people’s expertise and career

timelines, sometimes even more accurately than how they represent

themselves in CVs. Tambe was both resourceful and lucky. Today, you have

to be even more resourceful and creative.

Further Resources*

- Kaggle dataset of anonymized LinkedIn profiles

- Data.world LinkedIn dataset of top skills by year

- Data.world LinkedIn dataset on job data by US state

- A 2015 list of links to datasets of LinkedIn profiles on reddit

- Network repository LinkedIn dataset

- The World Bank LinkedIn dataset

- Harvested LinkedIn search data with recipe from getdata.io

- Explore LinkedIn membership by field of study and geography, 2017

- Statista’s LinkedIn user volume dataset

*Scraping web pages and using the LinkedIn API for research purposes violates LinkedIn’s terms and conditions.

This post originally appeared as Social scientists working with LinkedIn data, on the SAGE Ocean blog under a CC BY-NC 4.0 licence. Interested in utilising social media data? Check out the latest course from SAGE Campus – collecting social media data.

About the author

Daniela Duca works on new products

within SAGE Ocean, collaborating with startups to help them bring their

tools to market. Before joining SAGE, she worked with student and

researcher-led teams that developed new software tools and services,

providing business planning and market development guidance and support.

She designed and ran a 2-year programme offering innovation grants for

researchers working with publishers on new software services to support

the management of research data. She is also a visual artist, with

experience in financial technology and has a PhD in innovation

management. You can connect with Daniela on Twitter.

Note: This article gives the views of

the authors, and not the position of the LSE Impact Blog, nor of the

London School of Economics. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below

Image Credit, Dimitar Belchev via Unsplash (Licensed under a CC0 1.0 licence)

No comments:

Post a Comment