In the past academics and researchers have

had relatively few tools at hand for finding out which bits of their

work are appreciated and used by other academics. There are well-known,

first generation, proprietary citations tracking systems (like ISI Web

of Science and Scopus) that cover only or chiefly well-established

journals with long time-lags. In the digital-era there are also newer

Internet-based systems drawing extensively on Google which now offer a

much broader and more responsive picture of who is citing or using whom

in academia. Both types of systems have pros and cons that we will

discuss in detail, and we will give step-by-step guidance on how

academics can use the systems to look at their own work.

had relatively few tools at hand for finding out which bits of their

work are appreciated and used by other academics. There are well-known,

first generation, proprietary citations tracking systems (like ISI Web

of Science and Scopus) that cover only or chiefly well-established

journals with long time-lags. In the digital-era there are also newer

Internet-based systems drawing extensively on Google which now offer a

much broader and more responsive picture of who is citing or using whom

in academia. Both types of systems have pros and cons that we will

discuss in detail, and we will give step-by-step guidance on how

academics can use the systems to look at their own work.

Our best advice to researchers wanting to

find out how their work is being used by other academics is to use a

combination of the three best tools, which are:

find out how their work is being used by other academics is to use a

combination of the three best tools, which are:

- Harzing’s ‘Publish or Perish’ (HPoP) software, which is a

tweaked version of Google Scholar that delivers rapid feedback and

covers far more sources (and somewhat more diverse sources) than

anything else; - ISI Web of Science, which is most useful for senior

academics with a slate of published work already in high impact

journals, and for academics in the physical sciences; and - Google Book Search and Google Scholar for people working in disciplines where books and other non-journal academic outputs are important.

In the main body of this chapter we review

these three systems and quite a few alternatives in depth, and explain

how they work, what each of them is good for, their limitations, and how

to get the best possible results from each of them. Armed with our

advice notes we suggest that readers try out these systems and see which

ones seem to work best for their discipline and for tracking their

particular type of research.

these three systems and quite a few alternatives in depth, and explain

how they work, what each of them is good for, their limitations, and how

to get the best possible results from each of them. Armed with our

advice notes we suggest that readers try out these systems and see which

ones seem to work best for their discipline and for tracking their

particular type of research.

We begin with a small but key digression

on how to maximise finding an academic’s name in a search engine so that

her citations can be more easily tracked. Next we consider the older

citation tracking systems that focus only on (some) journal articles. In

section three we look at the new Internet-based systems.

on how to maximise finding an academic’s name in a search engine so that

her citations can be more easily tracked. Next we consider the older

citation tracking systems that focus only on (some) journal articles. In

section three we look at the new Internet-based systems.

If an academic has a distinctive author

name (with an uncommon surname and plenty of initials to identify her

uniquely) then it will easier to find out how many other authors are

citing her research. However, if an author has an indistinct name (like

Smith, Jones, Brown, Li, Dupont, etc. and only one initial), it will

take longer to obtain the same accurate information. It may not be

possible to efficiently use some of the best citation systems at all,

such as Harzing’s Publish or Perish (HPoP), and an academic may have to

piece together citations for each of their publications using the titles

to exclude references to many namesakes. A key implication arise here

for new researchers just starting out on academic career (or a mentor

advising a new researcher). She must choose her author name with great

care, using the full first name and adding her second name or initial if

applicable. Academics should keep in mind that from now on (for the

rest of their career) people will be looking for their work in a

global-sized haystack of competing information.

name (with an uncommon surname and plenty of initials to identify her

uniquely) then it will easier to find out how many other authors are

citing her research. However, if an author has an indistinct name (like

Smith, Jones, Brown, Li, Dupont, etc. and only one initial), it will

take longer to obtain the same accurate information. It may not be

possible to efficiently use some of the best citation systems at all,

such as Harzing’s Publish or Perish (HPoP), and an academic may have to

piece together citations for each of their publications using the titles

to exclude references to many namesakes. A key implication arise here

for new researchers just starting out on academic career (or a mentor

advising a new researcher). She must choose her author name with great

care, using the full first name and adding her second name or initial if

applicable. Academics should keep in mind that from now on (for the

rest of their career) people will be looking for their work in a

global-sized haystack of competing information.

In Britain and Europe generally there is a

huge extra problem to citation tracking arising from the restrictive

and old-fashioned practices of journal style sheets. Coming from mostly

small countries it is still common to find that most European social

science journals include only the first initials of authors in footnotes

or reference lists, so that they do not give authors’ first names in

full, nor include their second or subsequent initials. Since academic

knowledge is now organised on a global scale this is very bad practice.

In the US, where there are now over 300 million people, the demands of

finding people in a larger society have generally meant that much better

author details are included. This is a pattern that European academics

and journal editors should urgently start to copy.

huge extra problem to citation tracking arising from the restrictive

and old-fashioned practices of journal style sheets. Coming from mostly

small countries it is still common to find that most European social

science journals include only the first initials of authors in footnotes

or reference lists, so that they do not give authors’ first names in

full, nor include their second or subsequent initials. Since academic

knowledge is now organised on a global scale this is very bad practice.

In the US, where there are now over 300 million people, the demands of

finding people in a larger society have generally meant that much better

author details are included. This is a pattern that European academics

and journal editors should urgently start to copy.

ISI completely ignores a vast majority of publications in the social sciences and humanities. Anne-Will Harzing (2010)

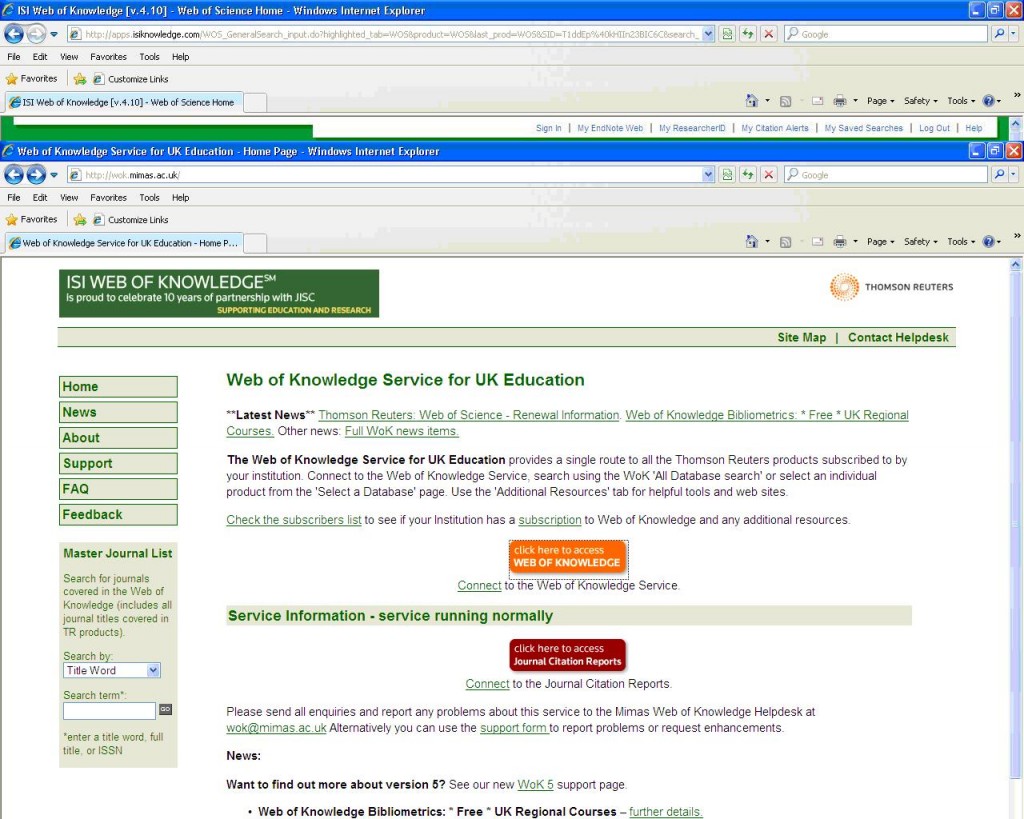

There are some well-established and

proprietary systems for tracking citations, also known as bibliometric

systems. Compiled by hand and run on mainframe computers, they started

as far back as the 1970s, and the best-known now is the ISI Web of

Knowledge (which has a Social Science Citation Index). Its main rival is

the less well known Scopus. Since these mainframe systems went online

they have become a lot more accessible and somewhat easier to use. Most

academics, post-docs and PhD students should now be able to access one

of them from their offices or home computers via their university

library. (Few libraries will pay for both of them, because their

subscriptions are expensive).

proprietary systems for tracking citations, also known as bibliometric

systems. Compiled by hand and run on mainframe computers, they started

as far back as the 1970s, and the best-known now is the ISI Web of

Knowledge (which has a Social Science Citation Index). Its main rival is

the less well known Scopus. Since these mainframe systems went online

they have become a lot more accessible and somewhat easier to use. Most

academics, post-docs and PhD students should now be able to access one

of them from their offices or home computers via their university

library. (Few libraries will pay for both of them, because their

subscriptions are expensive).

The companies that produce these systems

(Thompson for ISI and Elsevier for Scopus) rightly stress that they are

well-established and well-founded on decades of experience. The systems

give accurate citation counts (without duplications or phantom

citations) because they are human-edited systems – one reason why they

are also expensive to produce and hence are charged for. Above all they

emphasise that the carefully guarded portals of the ISI and Scopus only

include academically verified journals and exclude irrelevant or

non-standard sources. However, there are conflicts of interest in Scopus

being run by a company that is itself a major global journal publisher.

Both databases also have a strong vested interest in running their

operations in a restrictive way, to protect their costly proprietary

model.

(Thompson for ISI and Elsevier for Scopus) rightly stress that they are

well-established and well-founded on decades of experience. The systems

give accurate citation counts (without duplications or phantom

citations) because they are human-edited systems – one reason why they

are also expensive to produce and hence are charged for. Above all they

emphasise that the carefully guarded portals of the ISI and Scopus only

include academically verified journals and exclude irrelevant or

non-standard sources. However, there are conflicts of interest in Scopus

being run by a company that is itself a major global journal publisher.

Both databases also have a strong vested interest in running their

operations in a restrictive way, to protect their costly proprietary

model.

University hierarchs and government

research boards love the solid, IBM-era technology of these systems, and

view their costliness as a sign of quality. In addition, there is a

whole sub-community of scholars and consultants who have grown up to

analyse scientific referencing, especially in the physical sciences.

Practitioners in this sub-field of library science have invested a lot

of intellectual capital in learning how to use these large systems.

Because it requires years of apprenticeship to extract meaningful data

from ISI and Scopus, most bibliometrics experts favour a strategy that

presents their data as comprehensive of the best journals. This has

hindered the development and recognition of newer internet-based systems

and approaches.

research boards love the solid, IBM-era technology of these systems, and

view their costliness as a sign of quality. In addition, there is a

whole sub-community of scholars and consultants who have grown up to

analyse scientific referencing, especially in the physical sciences.

Practitioners in this sub-field of library science have invested a lot

of intellectual capital in learning how to use these large systems.

Because it requires years of apprenticeship to extract meaningful data

from ISI and Scopus, most bibliometrics experts favour a strategy that

presents their data as comprehensive of the best journals. This has

hindered the development and recognition of newer internet-based systems

and approaches.

Conventional citation systems like ISI and

Scopus have some severe limitations that need to be kept in

mind-especially by social scientists and academics in the humanities –

because these systems cover only a limited number of journals, and no or

few books. In addition, the indexing criteria for journals are lengthy

and heavily weighted towards journals that have already accumulated a

critical mass of citations from journals that are already in the index.

Scopus have some severe limitations that need to be kept in

mind-especially by social scientists and academics in the humanities –

because these systems cover only a limited number of journals, and no or

few books. In addition, the indexing criteria for journals are lengthy

and heavily weighted towards journals that have already accumulated a

critical mass of citations from journals that are already in the index.

The two conventional systems have a heavy

bias in coverage towards English-language and towards older established

journals. ISI especially is heavily American- dominated. Because the US

is a large and rich society, with many more academics in most social

science fields than in Europe or any other region of the world, the

conventional systems automatically tend to deliver rankings and

statistics that are weighted heavily towards success in the US ‘market’,

compared with the rest of the world. The ISI system does not cover

references in books, (although it does cover some book reviews in

journals). The Scopus System covers Book Series. Excluding books is a

fairly small problem in the physical sciences, which explains why the

ISI systems are set up in this way. But it is an insurmountably serious

limitation across the humanities where books are the main mode of

scholarly communication and a key vehicle of disciplinary development.

The lack of book coverage poses is a serious difficulties for accurately

measuring citations within ‘softer’ social science fields where books

remain very important.

bias in coverage towards English-language and towards older established

journals. ISI especially is heavily American- dominated. Because the US

is a large and rich society, with many more academics in most social

science fields than in Europe or any other region of the world, the

conventional systems automatically tend to deliver rankings and

statistics that are weighted heavily towards success in the US ‘market’,

compared with the rest of the world. The ISI system does not cover

references in books, (although it does cover some book reviews in

journals). The Scopus System covers Book Series. Excluding books is a

fairly small problem in the physical sciences, which explains why the

ISI systems are set up in this way. But it is an insurmountably serious

limitation across the humanities where books are the main mode of

scholarly communication and a key vehicle of disciplinary development.

The lack of book coverage poses is a serious difficulties for accurately

measuring citations within ‘softer’ social science fields where books

remain very important.

The older systems completely exclude

references in working papers or conference papers, and hence have very

long time lags. Publishing in a journal across the social sciences

generally takes a minimum of two years from submission to publication,

and often up to 3.5 years in the most competitive and technical fields

like economics. In the interim, conference papers and working papers

often provide many indications of how much work is being cited. But

neither type of outputs is included in the ISI, nor in the Scopus index.

Rather than reflecting the latest advances in academic research, these

systems tend to reflect the output component of the discipline three or

four years in the past. As a result of all these factors, ISI and

Scopus only cover a low fraction of academic journal papers in social

science published worldwide, and far less than the coverage in the

physical sciences, which can be regarded as near complete.

references in working papers or conference papers, and hence have very

long time lags. Publishing in a journal across the social sciences

generally takes a minimum of two years from submission to publication,

and often up to 3.5 years in the most competitive and technical fields

like economics. In the interim, conference papers and working papers

often provide many indications of how much work is being cited. But

neither type of outputs is included in the ISI, nor in the Scopus index.

Rather than reflecting the latest advances in academic research, these

systems tend to reflect the output component of the discipline three or

four years in the past. As a result of all these factors, ISI and

Scopus only cover a low fraction of academic journal papers in social

science published worldwide, and far less than the coverage in the

physical sciences, which can be regarded as near complete.

Figure 2.1 assesses the effects of ISI’s limited coverage of social science research. It captures the internal coverage

of the ISI databases in 2006 by showing the percentage of references

made in ISI articles that were made to journal articles already included

in the database.

of the ISI databases in 2006 by showing the percentage of references

made in ISI articles that were made to journal articles already included

in the database.

Figure 2.1: How

far the ISI Citation Indexes for 2006 include the references cited by

articles contained in the database across groups of related disciplines

far the ISI Citation Indexes for 2006 include the references cited by

articles contained in the database across groups of related disciplines

| Percentage of references cited in the ISI databaset hat are to other items included in the database | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| High (80-100%) | Medium (60-80%) | Low (40-60%) | Very low (less than 40%) |

| Molecular biology and biochemistry (90%) | Applied physics and chemistry | Mathematics (64%) | Languages and communication (32 to 40%) |

| Biological Sciences - humans (82 to 99%) | Biological sciences - animals and plants (c 75%) | Engineering (45 to 69%) | All other social sciences (24 to 36%) |

| Chemistry (88%) | Psychology and psychiatry (c.72%) | Computer sciences (43%) | Humanities and arts (11 to 27%) |

| Clinical medicine (85%) | Geosciences (62 to 74%) | Economics (43%) | |

| Physics and astronomy (84 to 86%) | Social sciences in medicine (62%) | ||

Source: Centre for Science and Technology Studies, 2007, Tables 3.1 and 3.3.

If ISI is capturing as it claims the most

important work in a field, then most of these references should be to

articles elsewhere in the ISI database. Figure 3.1 shows that ISI’s

internal coverage was indeed high in the medical and physical sciences,

for instance over 90 per cent in physics. Across other STEM disciplines

from four fifths to nearly all of the references are included. In more

applied physical science fields this proportion falls to two thirds or

three fifths, and in maths and engineering to between two and three

fifths, a level that is relatively lower. Social sciences, however, are

strongly affected by ISI’s coverage bias. With the exception of social

sciences related to medicine, coverage for the rest of social sciences

falls below 50%; for example, 43% for economics and between 24-36% for.

The humanities are the most affected with only 11-27% of internal

coverage. Most bibliometric experts acknowledge that the usefulness of

these systems declines sharply if they include fewer than three quarters

to two thirds of all journal articles world-wide.

important work in a field, then most of these references should be to

articles elsewhere in the ISI database. Figure 3.1 shows that ISI’s

internal coverage was indeed high in the medical and physical sciences,

for instance over 90 per cent in physics. Across other STEM disciplines

from four fifths to nearly all of the references are included. In more

applied physical science fields this proportion falls to two thirds or

three fifths, and in maths and engineering to between two and three

fifths, a level that is relatively lower. Social sciences, however, are

strongly affected by ISI’s coverage bias. With the exception of social

sciences related to medicine, coverage for the rest of social sciences

falls below 50%; for example, 43% for economics and between 24-36% for.

The humanities are the most affected with only 11-27% of internal

coverage. Most bibliometric experts acknowledge that the usefulness of

these systems declines sharply if they include fewer than three quarters

to two thirds of all journal articles world-wide.

In addition, how far does ISI’s strong

orientation towards American journals affect coverage when we come to

look at research undertaken in other countries, like the UK. A detailed

analysis was undertaken of the research submitted to the UK’s Research

Assessment Exercise for 2001 (covering publications in 1996-2000),

providing a useful external measure of coverage. It found that the ISI

database included five out of every six RAE items submitted in the

physical sciences (the STEM disciplines) , but only one in four items

for the social sciences, as Figure 2.2 demonstrates. These numbers are

very similar to the ISI internal coverage numbers above, even though

they relate to different dates. So the internal coverage estimates for

the database as a whole and the UK-specific external estimates of

coverage offer a similar picture.

orientation towards American journals affect coverage when we come to

look at research undertaken in other countries, like the UK. A detailed

analysis was undertaken of the research submitted to the UK’s Research

Assessment Exercise for 2001 (covering publications in 1996-2000),

providing a useful external measure of coverage. It found that the ISI

database included five out of every six RAE items submitted in the

physical sciences (the STEM disciplines) , but only one in four items

for the social sciences, as Figure 2.2 demonstrates. These numbers are

very similar to the ISI internal coverage numbers above, even though

they relate to different dates. So the internal coverage estimates for

the database as a whole and the UK-specific external estimates of

coverage offer a similar picture.

Figure 2.2: The inclusiveness of the ISI database for items submitted to the UK’s Research Assessment Exercise of 2001

A final dimension to consider for the

social sciences concerns the trends over time – has the ISI got better

at including social science materials? Do its continuing problems

perhaps reflect chiefly its origins in the physical sciences and

initially rather restrictive approach to including journals? As the

database has expanded along with the growth of social sciences journals

and publishing, has it become any more inclusive? Figure 2.3 shows how

the detailed ISI internal coverage of the social science disciplines

changed over a decade and a half. There has indeed been a general

substantial improvement in coverage of these disciplines, but one

starting from a pretty low base. By contrast, in humanities subjects the

ISI’s inclusiveness has generally either declined or increased only

slightly. Subjects bridging from the social sciences into STEM

disciplines also show increases in internal coverage, but with smaller

percentage changes because they start from a higher initial base.

social sciences concerns the trends over time – has the ISI got better

at including social science materials? Do its continuing problems

perhaps reflect chiefly its origins in the physical sciences and

initially rather restrictive approach to including journals? As the

database has expanded along with the growth of social sciences journals

and publishing, has it become any more inclusive? Figure 2.3 shows how

the detailed ISI internal coverage of the social science disciplines

changed over a decade and a half. There has indeed been a general

substantial improvement in coverage of these disciplines, but one

starting from a pretty low base. By contrast, in humanities subjects the

ISI’s inclusiveness has generally either declined or increased only

slightly. Subjects bridging from the social sciences into STEM

disciplines also show increases in internal coverage, but with smaller

percentage changes because they start from a higher initial base.

Figure 2.3: How

far the ISI Citation Indexes have improved over time in their including

the references cited by articles contained in the database across social

science and neighbouring disciplines, from 1991 to 2006

far the ISI Citation Indexes have improved over time in their including

the references cited by articles contained in the database across social

science and neighbouring disciplines, from 1991 to 2006

| ISI's internal coverage (%) in | Percentage change 1991 to 2006 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 1991 | % | |

| For comparison: Life sciences | 93 | 87 | 7 |

| Psychology | 72 | 59 | 22 |

| Health sciences | 62 | 50 | 24 |

| Computer sciences | 43 | 38 | 13 |

| Economics | 43 | 35 | 23 |

| Inter-disciplinary social sciences | 40 | 33 | 21 |

| Languages and linguistics | 40 | 26 | 54 |

| Educational sciences | 36 | 27 | 33 |

| Management, Planning | 36 | 23 | 57 |

| Law, Criminology | 31 | 27 | 15 |

| Sociology, Anthropology | 34 | 22 | 55 |

| Information science, Communication science | 32 | 32 | 0 |

| History, Philosophy, Religion | 27 | 24 | 13 |

| Political science, Public administration | 24 | 17 | 41 |

| Creative arts, Culture, Music | 14 | 17 | -18 |

| Literature | 11 | 14 | -21 |

Source: The data in the first three columns are from Centre for Science and Technology Studies, 2007, Table 3.3.

Notes: ‘Internal coverage’ means the percentage of references

cited in articles in the ISI database that are to other items included

in the database. The yellow-shaded rows here are those for social

sciences, green for humanities, and blue for subjects that are primarily

physical sciences or STEM subjects.

Notes: ‘Internal coverage’ means the percentage of references

cited in articles in the ISI database that are to other items included

in the database. The yellow-shaded rows here are those for social

sciences, green for humanities, and blue for subjects that are primarily

physical sciences or STEM subjects.

For many years the known deficiencies of

the ISI databases in the social sciences were routinely acknowledged,

but none the less were put somewhat on one side because the data

represented one of the only sources of insight. However, in the modern

era where there are viable alternatives (indeed superior options for

most social scientists) this stance is no longer appropriate.

Bibliometricians commissioned by the UK’s Higher Education Funding

Council to help them consider the use of citations data recommended that

it was not appropriate to rely on conventional citations systems like

ISI unless the internal coverage of items approached four fifths (the

‘high’ level in Figure 3.1) (Centre for Science and Technology, 2007,

pp.xx-xx). The lower that coverage gets in a field, the less useful ISI

ratings could be for assessing scholarly performance. They recommended

that in disciplines where less than 50 per cent of references are being

included in ISI, citations analysis could not contribute reliable

information to a research assessment process.

the ISI databases in the social sciences were routinely acknowledged,

but none the less were put somewhat on one side because the data

represented one of the only sources of insight. However, in the modern

era where there are viable alternatives (indeed superior options for

most social scientists) this stance is no longer appropriate.

Bibliometricians commissioned by the UK’s Higher Education Funding

Council to help them consider the use of citations data recommended that

it was not appropriate to rely on conventional citations systems like

ISI unless the internal coverage of items approached four fifths (the

‘high’ level in Figure 3.1) (Centre for Science and Technology, 2007,

pp.xx-xx). The lower that coverage gets in a field, the less useful ISI

ratings could be for assessing scholarly performance. They recommended

that in disciplines where less than 50 per cent of references are being

included in ISI, citations analysis could not contribute reliable

information to a research assessment process.

Bearing in mind ISI’s

limited coverage and geographical bias, academics should interpret ISI

citation data with some degree of caution. In the social sciences ISI

does not in any sense provide a more accurate insight into the overall

and global impacts of academic work than newer internet-based systems.

It can offer, however, a somewhat better picture of academic impact for

those disciplines which tend to focus on high-prestige American-based

journal articles. As the US is still normally rated as the first or

second most influential country in the world across all social science

disciplines, this is an important consideration.

limited coverage and geographical bias, academics should interpret ISI

citation data with some degree of caution. In the social sciences ISI

does not in any sense provide a more accurate insight into the overall

and global impacts of academic work than newer internet-based systems.

It can offer, however, a somewhat better picture of academic impact for

those disciplines which tend to focus on high-prestige American-based

journal articles. As the US is still normally rated as the first or

second most influential country in the world across all social science

disciplines, this is an important consideration.

Box 2a explains how to access ISI and the

somewhat complicated processes that are normally necessary to extract a

record from it of how your work has been cited:

somewhat complicated processes that are normally necessary to extract a

record from it of how your work has been cited:

Box 2a: How to use the ISI Web of Science

Gaining access will usually

require going to your library’s website and following a link to the

online version of ISI that you can operate from your desktop in your

office or home office. Once you are logged on:

require going to your library’s website and following a link to the

online version of ISI that you can operate from your desktop in your

office or home office. Once you are logged on:

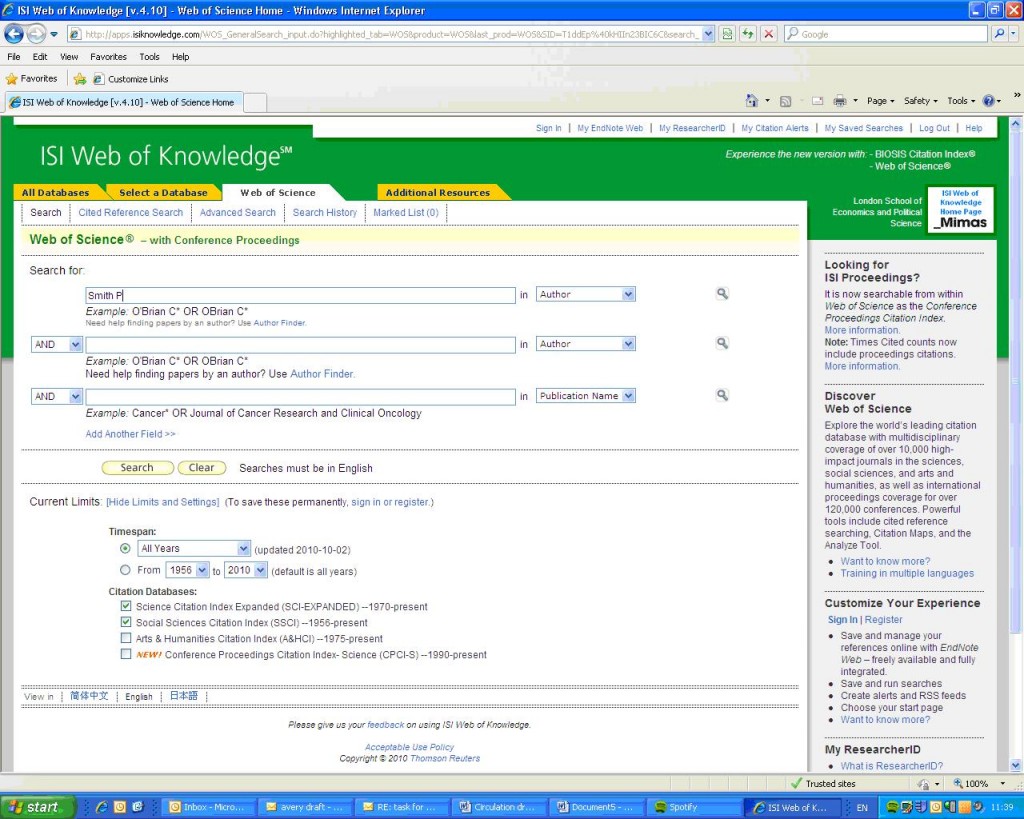

Step 1: Click the button to access the Web of

Knowledge. First use the “Select A Database” tab on the top right of the

screen and click on Web of Science. One of the most confusing aspects

of the ISI website is its proliferation of differently named databases

(all sitting on different mainframes). These names obviously mean a lot

to ISI and bibliometrics experts but they are just confusing ‘chaff’ for

normal users. You can choose to look across four citation indexes or

only choose the ones you want.

Step 2: Input the author

name you are searching for, your own or someone else’s. It is important

to do it in the restrictive (old-fashioned) format suggested by the

software. For example, if your name is ‘Peter Smith’, you will have to

enter ‘Smith P’.

name you are searching for, your own or someone else’s. It is important

to do it in the restrictive (old-fashioned) format suggested by the

software. For example, if your name is ‘Peter Smith’, you will have to

enter ‘Smith P’.

Step 3: The outputs from the

software will include each article name, journal title, volume, issue,

pages, publishing year and times cited. The most important parameter to

understand the academic impact of a researcher is the times each piece

of work is cited.To read, store and analyse the data in a more

convenient program like Excel, and to ‘clean’ it of misleading materials

and statistics, do the following

software will include each article name, journal title, volume, issue,

pages, publishing year and times cited. The most important parameter to

understand the academic impact of a researcher is the times each piece

of work is cited.To read, store and analyse the data in a more

convenient program like Excel, and to ‘clean’ it of misleading materials

and statistics, do the following

Step 4: Scroll to the bottom of the page and under Step 1 of “Output Records” select “All records on page”.

Step 5: Under Step 2 of “Output Records” deselect “plus Abstract”.

Step 6: Under Step 3 of “Output

Records” in “Save to other reference software” pick “save to Tab

delimited (win)” (or Mac if you have a Mac).

Records” in “Save to other reference software” pick “save to Tab

delimited (win)” (or Mac if you have a Mac).

Step 7: A Notepad file will be

created that you can either open immediately or save onto your desktop.

With two or more screens of data you need to past each screen into

Notepad in sequence and then save it.

created that you can either open immediately or save onto your desktop.

With two or more screens of data you need to past each screen into

Notepad in sequence and then save it.

Step 8: If you now open the

Notepad file and highlight and copy its full contents you can then just

paste them directly into Excel – the data and text will come into Excel

fully formatted.

Notepad file and highlight and copy its full contents you can then just

paste them directly into Excel – the data and text will come into Excel

fully formatted.

Step 9: Alternatively you can

import your saved Notepad file into Excel. You will be prompted to

complete three steps to import the data

import your saved Notepad file into Excel. You will be prompted to

complete three steps to import the data

(a) Select “delimited”

(b) Select “Tab”

(c) Just click on FINISH

(b) Select “Tab”

(c) Just click on FINISH

Step 10: You could archive the

whole resulting file and then copy the records to a new worksheet where

you can construct a summary tile. Delete any columns that are of no

interest to you. Normally it will be enough to retain the publication

name, authors, publication year, and times cited.

whole resulting file and then copy the records to a new worksheet where

you can construct a summary tile. Delete any columns that are of no

interest to you. Normally it will be enough to retain the publication

name, authors, publication year, and times cited.

Step 11: If you have written a lot

of book reviews in journals they will be included as items in the ISI

lists. But such single reviews are almost never cited by anyone. Hence

they will always act to depress your ‘times cited’ average. To get rid

of them, and get a better picture, sort the ISI entries in Excel in

descending order of times cited, so as to group all the zero cited items

together at the end of the list. Copy the sorted full data to a new

worksheet in the same file, and then delete the book reviews from the

end to give a new listing of just genuine journal articles.

of book reviews in journals they will be included as items in the ISI

lists. But such single reviews are almost never cited by anyone. Hence

they will always act to depress your ‘times cited’ average. To get rid

of them, and get a better picture, sort the ISI entries in Excel in

descending order of times cited, so as to group all the zero cited items

together at the end of the list. Copy the sorted full data to a new

worksheet in the same file, and then delete the book reviews from the

end to give a new listing of just genuine journal articles.

ISI can be a helpful system for expanding

normal literature review searches. However, it doesn’t provide the very

helpful ‘snippet-view’ materials that Google Scholar does, which can be

very helpful in ascertaining what a paper is about if it has an obscure

title, and which are more helpful for checking through the backlist

works of particular authors. But ISI does provide a relatively useful

means of checking for key terms in article titles. It has a good date

record and hence is an effective way of surfacing some of the main

journal articles with keywords in their titles in say the last 5 or 10

years, often the most relevant search periods.

normal literature review searches. However, it doesn’t provide the very

helpful ‘snippet-view’ materials that Google Scholar does, which can be

very helpful in ascertaining what a paper is about if it has an obscure

title, and which are more helpful for checking through the backlist

works of particular authors. But ISI does provide a relatively useful

means of checking for key terms in article titles. It has a good date

record and hence is an effective way of surfacing some of the main

journal articles with keywords in their titles in say the last 5 or 10

years, often the most relevant search periods.

Google has been the prime force in the

development of article-finding, book-finding and citations-tracking

systems free over the Internet, having ambitiously declared its mission

to ‘to organise the world’s information.’ Less than a decade after its

founding, the company’s twin academic research engines Google Scholar (for journal articles and other academic papers) and Google Books now dominate the university sector.

development of article-finding, book-finding and citations-tracking

systems free over the Internet, having ambitiously declared its mission

to ‘to organise the world’s information.’ Less than a decade after its

founding, the company’s twin academic research engines Google Scholar (for journal articles and other academic papers) and Google Books now dominate the university sector.

There are other similar internet-based systems. The nearest counterpart to Google Scholar is the little-known Scirus

system from Elsevier, a free-to-use counterpart to their Scopus system

which draws more widely on current working papers and conference papers.

It operates similarly to Scholar and is worth checking as an additional

source. In the US there are some other Scholar competitor sites, but

they all rely on academics registering and voluntarily uploading

materials. As many academics are unlikely to do this, the coverage of

these sites (like CiteSeerX and getCITED) is now far too restricted and

non-comprehensive to be very useful.

system from Elsevier, a free-to-use counterpart to their Scopus system

which draws more widely on current working papers and conference papers.

It operates similarly to Scholar and is worth checking as an additional

source. In the US there are some other Scholar competitor sites, but

they all rely on academics registering and voluntarily uploading

materials. As many academics are unlikely to do this, the coverage of

these sites (like CiteSeerX and getCITED) is now far too restricted and

non-comprehensive to be very useful.

The current dominance of automatic search

systems like Google Scholar (also an approach used by Scirus) derives

from the fact that they voraciously and automatically record all citations. In particular they include:

systems like Google Scholar (also an approach used by Scirus) derives

from the fact that they voraciously and automatically record all citations. In particular they include:

- all ‘black’ literature in journal articles or books that has been definitively and formally published, plus

- less conventional ‘grey’ literature, such as working papers,

conference papers, seminar discussions or teaching materials that has

been issued in a less formal or definitive form – often, of course,

including versions of material that is later formally published.

This inclusiveness makes Google Scholar

far more up-to-date in its picture of academic debates and controversies

in each discipline, especially so in fields like computer science and

IT studies where the pace of change in technologies and social uses of

IT is very rapid. Scholar also gives users much more immediate

information about the work being found, and it often gives full-text

access to it if the material is not in a published book or placed behind

a journal pay wall.

far more up-to-date in its picture of academic debates and controversies

in each discipline, especially so in fields like computer science and

IT studies where the pace of change in technologies and social uses of

IT is very rapid. Scholar also gives users much more immediate

information about the work being found, and it often gives full-text

access to it if the material is not in a published book or placed behind

a journal pay wall.

The dominance of automatic systems has

been strengthened (and the obsolescing of American voluntary

article-aggregator sites has been speeded up) by the growth of online

research depositories in most serious universities in the advanced

industrial countries. These university archives now host copies of their

professors’ and lecturers’ works that previously were accessible only

with great difficulty (by going to each individual author’s personal

website) or behind journal pay walls. University online depositories

also often contain conference and working papers that have not yet been

formally published in journals, which Scholar and Scirus can both access

and provide immediate full text access to.

been strengthened (and the obsolescing of American voluntary

article-aggregator sites has been speeded up) by the growth of online

research depositories in most serious universities in the advanced

industrial countries. These university archives now host copies of their

professors’ and lecturers’ works that previously were accessible only

with great difficulty (by going to each individual author’s personal

website) or behind journal pay walls. University online depositories

also often contain conference and working papers that have not yet been

formally published in journals, which Scholar and Scirus can both access

and provide immediate full text access to.

Another useful development for Scholar and

Scirus has been the development of some important multi-institutional

sources hosting key research in pre-journal forms for free download. In

the physical sciences newsletters and research feeds now often sustain a

vigorous window into professional culture and current developments. In

the social sciences these networks are somewhat less developed, but

research paper depositories are big news. Two of the most important are

the multi-field Social Science Research Network (SSRN) and in American

economics the National Bureau for Economic Research (NBER),. But there

are many others.

Scirus has been the development of some important multi-institutional

sources hosting key research in pre-journal forms for free download. In

the physical sciences newsletters and research feeds now often sustain a

vigorous window into professional culture and current developments. In

the social sciences these networks are somewhat less developed, but

research paper depositories are big news. Two of the most important are

the multi-field Social Science Research Network (SSRN) and in American

economics the National Bureau for Economic Research (NBER),. But there

are many others.

For assessing citations in journal

articles, papers and related materials, at first sight it seems clear

that Scholar and Scirus should be the most useful search tools. However,

there are also four significant problems.

articles, papers and related materials, at first sight it seems clear

that Scholar and Scirus should be the most useful search tools. However,

there are also four significant problems.

1) Both the Scholar and Scirus systems

clearly access a range of mainly academic sources, but unlike ISI and

Scopus neither company provides any full specification of exactly which

sources they use. Scholar clearly searches many conventional academic

index systems, as well as journals’ and publishers’ websites, conference

proceedings, university sites and depositories and other web-accessible

materials in academic contexts. But Google provides almost no

information on exactly how this is done. This non-disclosure creates a

big problem for government or professional bodies, and feeds their

resolution not to take what Google says on trust.

clearly access a range of mainly academic sources, but unlike ISI and

Scopus neither company provides any full specification of exactly which

sources they use. Scholar clearly searches many conventional academic

index systems, as well as journals’ and publishers’ websites, conference

proceedings, university sites and depositories and other web-accessible

materials in academic contexts. But Google provides almost no

information on exactly how this is done. This non-disclosure creates a

big problem for government or professional bodies, and feeds their

resolution not to take what Google says on trust.

2) For commercial reasons Google and

Scirus are both equally secretive about the algorithms that they use to

sort and search, in particular to discount duplicate entries for the

same material, and how they count the remaining citations (after

duplicates are removed). This is a highly sensitive subject and adds

another barrier. However, the companies also argue that only by keeping

their algorithms secret can they effectively counter spam, which is a

growing and huge problem. Clearly if the ranking of sites could be

distorted by spammers, the usefulness of Scholar or alternatives would

be completely devalued.

Scirus are both equally secretive about the algorithms that they use to

sort and search, in particular to discount duplicate entries for the

same material, and how they count the remaining citations (after

duplicates are removed). This is a highly sensitive subject and adds

another barrier. However, the companies also argue that only by keeping

their algorithms secret can they effectively counter spam, which is a

growing and huge problem. Clearly if the ranking of sites could be

distorted by spammers, the usefulness of Scholar or alternatives would

be completely devalued.

3) Critics argue that because Scholar and

Scirus are automated systems they sweep up together lots of different

academic sources, some major journal articles, key professional

conferences or major university e-depositories, but others quite likely

of questionable academic status and provenance. So citations become

blurred and over-inclusive, with far more marked variations in the

‘academic value’ or ‘research’ status of different citations than occur

within the walled gardens of the ISI database.

Scirus are automated systems they sweep up together lots of different

academic sources, some major journal articles, key professional

conferences or major university e-depositories, but others quite likely

of questionable academic status and provenance. So citations become

blurred and over-inclusive, with far more marked variations in the

‘academic value’ or ‘research’ status of different citations than occur

within the walled gardens of the ISI database.

4) Another problem with these systems is

that they cannot recognise duplicated outputs, for example, a paper that

is available both on a standard journal website and on the author’s

personal website. This has implications for accurately counting the

number of outputs and citations.

that they cannot recognise duplicated outputs, for example, a paper that

is available both on a standard journal website and on the author’s

personal website. This has implications for accurately counting the

number of outputs and citations.

These are indeed serious problems if the

purpose of accessing Google Scholar (or Scirus) were to rank scholars’

standing or citations to their research comparatively, or if its

rankings were used to allocate rewards like research support funding

between departments or universities. However, we have chosen to focus on

two distinct features of these systems:

purpose of accessing Google Scholar (or Scirus) were to rank scholars’

standing or citations to their research comparatively, or if its

rankings were used to allocate rewards like research support funding

between departments or universities. However, we have chosen to focus on

two distinct features of these systems:

- allowing individual academics and researchers, or teams and departments to track their own citations; and

- expanding literature searches of other authors’ or researchers’ main works.

For both purposes, these four key problems

are still worth bearing in mind, but they are only limitations that

emphasise the need for individual judgement by the person consulting

them. Authors and research teams know their own work better than anyone

else in the world, and are therefore better able to analyse the data.

are still worth bearing in mind, but they are only limitations that

emphasise the need for individual judgement by the person consulting

them. Authors and research teams know their own work better than anyone

else in the world, and are therefore better able to analyse the data.

In addition, there are now simplified and

tweaked forms of accessing Google Scholar, of which the most important

is the ‘Public or Perish’ software available for free download from www.harzing.com/pop.htm.

This is a valuable programme that combats many of the problems of

interpreting Google Scholar outputs and allows academics to easily check

their own or others’ performance.. It presents academic outputs quickly

and computes excellent citation statistics about each author’s work,

including a overall ‘times cited’ score and times cited per year since

publication. We will continue the discussion of the more complex

versions of HPoP citation statistics in section 2.4. Box 2b explains

how to download and use the programme.

tweaked forms of accessing Google Scholar, of which the most important

is the ‘Public or Perish’ software available for free download from www.harzing.com/pop.htm.

This is a valuable programme that combats many of the problems of

interpreting Google Scholar outputs and allows academics to easily check

their own or others’ performance.. It presents academic outputs quickly

and computes excellent citation statistics about each author’s work,

including a overall ‘times cited’ score and times cited per year since

publication. We will continue the discussion of the more complex

versions of HPoP citation statistics in section 2.4. Box 2b explains

how to download and use the programme.

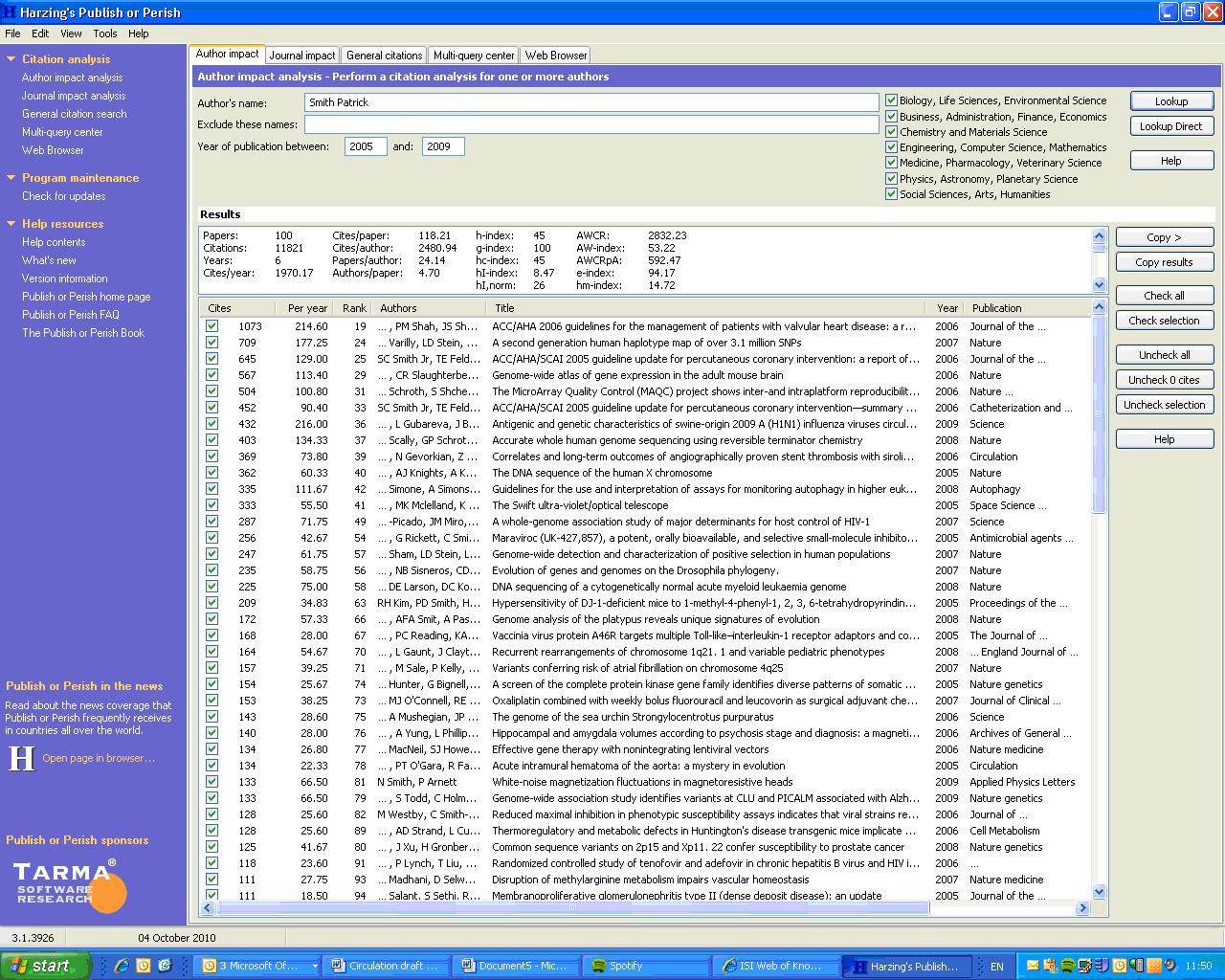

Box 2b: How to use Harzing’s ‘Publish or Perish’ software

Step 1: Download the software for free from www.harzing.com

Step 2: Launch the application from your desktop.

Step 3: Choose ‘Author Impact Analysis’

Step 4: Enter the name you want as surname, firstname. (Capitalization is not necessary.)

Step 5: The statistical indicators

for that author will be displayed in the upper portion of the screen,

and a detailed list of works in the bottom panel, initially arranged in

descending order of total citations for works. You can rearrange the

order of the list of works by clicking any of the column headings here.

for that author will be displayed in the upper portion of the screen,

and a detailed list of works in the bottom panel, initially arranged in

descending order of total citations for works. You can rearrange the

order of the list of works by clicking any of the column headings here.

Step 6: Check the detailed list

for any irrelevant entries for other authors – exclude them from the

statistics by de-clicking the tick box in the leftmost column.

for any irrelevant entries for other authors – exclude them from the

statistics by de-clicking the tick box in the leftmost column.

Step7: If other authors have cited

your work in different ways (e.g. some include sub-titles and others

don’t, or get the title or name spelling wrong) there will be duplicate

entries. To eliminate (most of) these, click the ‘Title’ heading to

temporarily re-arrange items in alphabetical order of titles. Then work

through and when you find duplications, right click the duplicate item

to highlight it, and then move it to place it above the main reference

for that work: HPoP will now show these as one item. With several

duplicates, be careful to choose the most accurate one as the main

reference.

your work in different ways (e.g. some include sub-titles and others

don’t, or get the title or name spelling wrong) there will be duplicate

entries. To eliminate (most of) these, click the ‘Title’ heading to

temporarily re-arrange items in alphabetical order of titles. Then work

through and when you find duplications, right click the duplicate item

to highlight it, and then move it to place it above the main reference

for that work: HPoP will now show these as one item. With several

duplicates, be careful to choose the most accurate one as the main

reference.

Step 8: The list of works can be

saved in Excel format (comma delimited) or copied and pasted into Word.

The Word lists initially look a bit jumbled. They can be quickly

clarified by going to the very end of each entry (giving the URL for

that work) and clicking on one space to show the URL in clickable

format. Then click return to start the next entry on a new line.

saved in Excel format (comma delimited) or copied and pasted into Word.

The Word lists initially look a bit jumbled. They can be quickly

clarified by going to the very end of each entry (giving the URL for

that work) and clicking on one space to show the URL in clickable

format. Then click return to start the next entry on a new line.

Google Books

Google Books is a system that is primarily

designed to make available a range of different online views of a

book’s contents to potential readers. Essentially Google has now run

around 10 million books through optical character readers so as to

create online images of each page. For books that are out of copyright,

Google makes available the full text for reading online, but the

material cannot be downloaded in the free use version of the programme.

The text of most out of copyright books is also fully searchable, so you

can easily find specific sentences, quotations, or words of interest

anywhere in the book. This software is so powerful and so good that many

scholars now use Google Books as an online index to find material

within books that they already have on their shelves, but which have

either no index or the normally very inadequate academic book index

system. There are also links through from Google Books to the

publisher’s website, to booksellers offering the book, or to libraries

nearby to the searchers’ location that stock it.

designed to make available a range of different online views of a

book’s contents to potential readers. Essentially Google has now run

around 10 million books through optical character readers so as to

create online images of each page. For books that are out of copyright,

Google makes available the full text for reading online, but the

material cannot be downloaded in the free use version of the programme.

The text of most out of copyright books is also fully searchable, so you

can easily find specific sentences, quotations, or words of interest

anywhere in the book. This software is so powerful and so good that many

scholars now use Google Books as an online index to find material

within books that they already have on their shelves, but which have

either no index or the normally very inadequate academic book index

system. There are also links through from Google Books to the

publisher’s website, to booksellers offering the book, or to libraries

nearby to the searchers’ location that stock it.

For books in copyright how much

information is viewable on Google Books depends on what agreement the

book’s publisher has reached with them. The most restrictive ‘no

preview’ entry just replicates the publishers’ blurb and perhaps gives

the contents pages. The next most restrictive approach is a ‘snippet

view’ that offers only a few short glimpses of the book’s content, but

still allows readers to search the full text and to find relevant

material. If you want to find out if a book covers the kind of topic you

are interested in, even in snippet view you can very quickly check far

more material in a fraction of the time that would be needed for

previous literature searches. The most expansive Google Books preview

allows you to read many full pages of the text, but normally will leave

out some key chapters or sections. However, you can usually search

across the omitted sections as well as the full text pages (helpful for

knowing how much coverage a book gives to your topic of interest). But

again you cannot download a copy of the book in the free version.

information is viewable on Google Books depends on what agreement the

book’s publisher has reached with them. The most restrictive ‘no

preview’ entry just replicates the publishers’ blurb and perhaps gives

the contents pages. The next most restrictive approach is a ‘snippet

view’ that offers only a few short glimpses of the book’s content, but

still allows readers to search the full text and to find relevant

material. If you want to find out if a book covers the kind of topic you

are interested in, even in snippet view you can very quickly check far

more material in a fraction of the time that would be needed for

previous literature searches. The most expansive Google Books preview

allows you to read many full pages of the text, but normally will leave

out some key chapters or sections. However, you can usually search

across the omitted sections as well as the full text pages (helpful for

knowing how much coverage a book gives to your topic of interest). But

again you cannot download a copy of the book in the free version.

Eventually, Google Books will be available

worldwide in a commercial version that will make all copyrighted books

in its database available for download, of course in return for a fee

that will be agreed between Google, the publishers and universities.

Google will potentially have an enormous monopoly position here, in a

market that is bound to grow very strongly in size and value over the

next decade, as e-books take off. How governments in the US, Europe and

other regions of the world decide to regulate Google’s operations of

this key intermediary role will have very substantial consequences for

how academic research develops, especially in the most book-based

disciplines, such as the humanities and ‘softer’ social sciences.

worldwide in a commercial version that will make all copyrighted books

in its database available for download, of course in return for a fee

that will be agreed between Google, the publishers and universities.

Google will potentially have an enormous monopoly position here, in a

market that is bound to grow very strongly in size and value over the

next decade, as e-books take off. How governments in the US, Europe and

other regions of the world decide to regulate Google’s operations of

this key intermediary role will have very substantial consequences for

how academic research develops, especially in the most book-based

disciplines, such as the humanities and ‘softer’ social sciences.

Leaving these meta-issues on one side,

however, what concerns us here is the citations-counting capacity of

Google Books, and Box 2c explains how to use it.

however, what concerns us here is the citations-counting capacity of

Google Books, and Box 2c explains how to use it.

Box 2c: How to use Google Books

Step 1: Go to

http://books.google.co.uk. Alternatively go to the main Google site and

pull down the menu tab labelled ‘more’ on the left of the Google menu

bar and go to Books directly in the options menu.

http://books.google.co.uk. Alternatively go to the main Google site and

pull down the menu tab labelled ‘more’ on the left of the Google menu

bar and go to Books directly in the options menu.

Step 2: Enter the author name in

double quotes, as “Firstname Lastname” and search.You can also try it as

“Initial Lastname”. Search using the ‘Listwise’ (default) option that

shows a snippet about each item found.

double quotes, as “Firstname Lastname” and search.You can also try it as

“Initial Lastname”. Search using the ‘Listwise’ (default) option that

shows a snippet about each item found.

Step 3: When the Books search

results come back make a note of how many items are returned in the

initial count given at the top of the search list. It is generally

better to go with the version of the author name that yields most

results.

results come back make a note of how many items are returned in the

initial count given at the top of the search list. It is generally

better to go with the version of the author name that yields most

results.

Step 4: Check that the search

process is producing a close fit to the author you want and is not

cluttered up with works from many other authors. This is easy if the

author name is distinctive. If the author name is a commonplace one use

‘Advanced Search’ to exclude ‘confuser’ author names and perhaps to

require a field-specific word to be present – e.g. entering ‘politic’

for a political scientist, should capture almost all their work but

exclude non-political items.

process is producing a close fit to the author you want and is not

cluttered up with works from many other authors. This is easy if the

author name is distinctive. If the author name is a commonplace one use

‘Advanced Search’ to exclude ‘confuser’ author names and perhaps to

require a field-specific word to be present – e.g. entering ‘politic’

for a political scientist, should capture almost all their work but

exclude non-political items.

Step 5: When you have a basically

OK listing, print the citations pages off and go through manually

excluding any remaining ‘confuser’ entries. Unless you have a very

common author name or a great deal of citations, this takes hardly any

time to do. (You may also wish to separate out and count those

references that are to the author as a book editor rather than to the

author’s own writings).

OK listing, print the citations pages off and go through manually

excluding any remaining ‘confuser’ entries. Unless you have a very

common author name or a great deal of citations, this takes hardly any

time to do. (You may also wish to separate out and count those

references that are to the author as a book editor rather than to the

author’s own writings).

Step 6: Always click through to

the final Google Books page, and you will get a completely different

citations count, that is a fraction of the initial count. This appears

to be the count of citations excluding multiple cites. You will need to

deduct from it a number for the entries you have hand deleted.

the final Google Books page, and you will get a completely different

citations count, that is a fraction of the initial count. This appears

to be the count of citations excluding multiple cites. You will need to

deduct from it a number for the entries you have hand deleted.

Step7: If the author name is

impossible to untangle from a multitude of similar names, even in the

same field, you can try repeating the search above using their main book

or journal titles as the search items.

impossible to untangle from a multitude of similar names, even in the

same field, you can try repeating the search above using their main book

or journal titles as the search items.

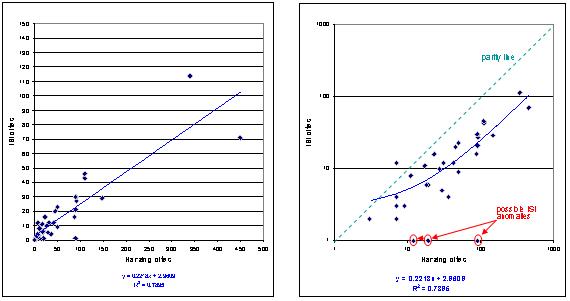

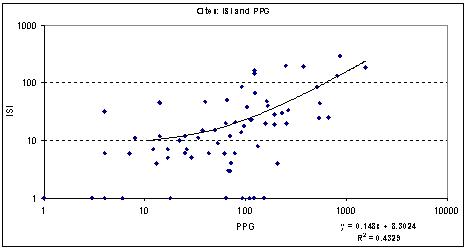

It is worth comparing how the two broad

categories of citations systems perform against each other. In general

the HPoP/Google Scholar database is much more inclusive than the ISI

one, especially in disciplines where books and book chapters are an

important means of professional communication. Figure 2.4 shows how the

ISI and HPoP indices compare. The top two parts show only the items

included in the ISI, first on a linear scale (which shows a strong

bunching of low-scoring items) and secondly on a logarithmic scale

(which helps to spread out the lower scores and shows the patterns of

data better). In every case the ISI cites score for a publication is

less than the HPoP/Google Scholar score (the point where they would be

equal being shown by the parity line).

categories of citations systems perform against each other. In general

the HPoP/Google Scholar database is much more inclusive than the ISI

one, especially in disciplines where books and book chapters are an

important means of professional communication. Figure 2.4 shows how the

ISI and HPoP indices compare. The top two parts show only the items

included in the ISI, first on a linear scale (which shows a strong

bunching of low-scoring items) and secondly on a logarithmic scale

(which helps to spread out the lower scores and shows the patterns of

data better). In every case the ISI cites score for a publication is

less than the HPoP/Google Scholar score (the point where they would be

equal being shown by the parity line).

Figure 2.4: The relationship between ISI and HPoP scores for one example academic, a senior professor in political science

Each blob represents one item’s citation scores

(a) Linear scales (coverage: ISI items only) (b) Log scales (coverage: ISI items only)

Notes: Figures 2.4a

and b include only items in the ISI database for this academic; Figure

2.4c includes all items in the person’s HPoP listing with at least three

cites. The HPoP scores have been manually cleaned to eliminate

duplicate Google Scholar entries.

and b include only items in the ISI database for this academic; Figure

2.4c includes all items in the person’s HPoP listing with at least three

cites. The HPoP scores have been manually cleaned to eliminate

duplicate Google Scholar entries.

Figure 2.4c shows the scores for all the

person’s HPoP scores. The items scoring high on HPoP but zero on the ISI

are in all cases comprised of books, book chapters and journal articles

in journals that are not indexed by ISI. Five of this author’s top 6

cited items fall into this category, and 12 of the person’s top 20 cited

pieces.

person’s HPoP scores. The items scoring high on HPoP but zero on the ISI

are in all cases comprised of books, book chapters and journal articles

in journals that are not indexed by ISI. Five of this author’s top 6

cited items fall into this category, and 12 of the person’s top 20 cited

pieces.

Of course, a single example of this kind

is only indicative, and so to get a broader picture we turn next to data

from the Impacts Project Database (IPD) described in Annex 1: Impacts Project Database.

Essentially we collated ISI and HPoP scores for all the traceable

publications of a sample of 120 academics spread across five social

science disciplines. We also carefully checked by hand all the

publications listed in HPoP/Scholar and looked at all the sources citing

them. We removed all duplicate entries, unacknowledged citations,

publishers’ publicity materials etc to produce a completely ‘cleaned’

IPD score, one that also incorporated citations in books. We aggregated

the ISI, HPoP and IPD scores for each academic concerned, and compared

them.

is only indicative, and so to get a broader picture we turn next to data

from the Impacts Project Database (IPD) described in Annex 1: Impacts Project Database.

Essentially we collated ISI and HPoP scores for all the traceable

publications of a sample of 120 academics spread across five social

science disciplines. We also carefully checked by hand all the

publications listed in HPoP/Scholar and looked at all the sources citing

them. We removed all duplicate entries, unacknowledged citations,

publishers’ publicity materials etc to produce a completely ‘cleaned’

IPD score, one that also incorporated citations in books. We aggregated

the ISI, HPoP and IPD scores for each academic concerned, and compared

them.

Figure 2.5: The inter-relationship between ISI and HPoP scores, and between ISI and IPD scores, for 100 academics in the IPD

Each mark represents one author’s aggregate citation scores. Graphs are log scaled.

(a)

(b)

(c) Correlation coefficients between the aggregate scores for authors

| ISI scores | Harzing scores | |

|---|---|---|

| Harzing scores | 0.22 (0.24) | |

| IPD scores | 0.14 (0.46) | 0.95** (0.0) |

Notes: Correlation coefficient (significance test, two-tailed).

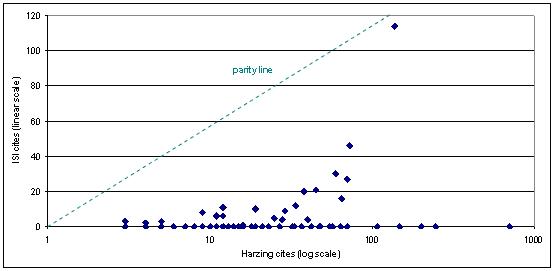

Figure 2.5 shows a strong continuity with

the picture drawn above. Most ISI cites scores for authors are much

lower than their HPoP scores, although it is noticeable that one in 10

of the sample showed ISI scores that are higher than their HPoP score.

One in twelve of the sample were rated by ISI as having a minimal score

of 1, whereas their HPoP scores ranged from 0 to 2089 cites. (On a per

author basis there are obviously fewer instances of ISI registering zero

cites than was the case for the per item basis in Figures 2.4a, or (b)

or (c).

the picture drawn above. Most ISI cites scores for authors are much

lower than their HPoP scores, although it is noticeable that one in 10

of the sample showed ISI scores that are higher than their HPoP score.

One in twelve of the sample were rated by ISI as having a minimal score

of 1, whereas their HPoP scores ranged from 0 to 2089 cites. (On a per

author basis there are obviously fewer instances of ISI registering zero

cites than was the case for the per item basis in Figures 2.4a, or (b)

or (c).

Figure 2.5b shows that this picture is

also strongly born out at the author level in the manually checked IPD

scores. The key reason for this is shown in Figure 2.5c, where the

HPoP/Scholar and IPD scores are shown to correlate almost perfectly (and

of course significantly). By contrast, the ISI scores correlated weakly

with the HPoP/Scholar scores for our sample, and even less well with

the carefully checked IPD scores.

also strongly born out at the author level in the manually checked IPD

scores. The key reason for this is shown in Figure 2.5c, where the

HPoP/Scholar and IPD scores are shown to correlate almost perfectly (and

of course significantly). By contrast, the ISI scores correlated weakly

with the HPoP/Scholar scores for our sample, and even less well with

the carefully checked IPD scores.

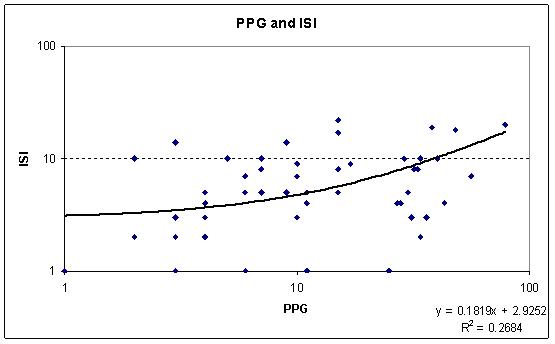

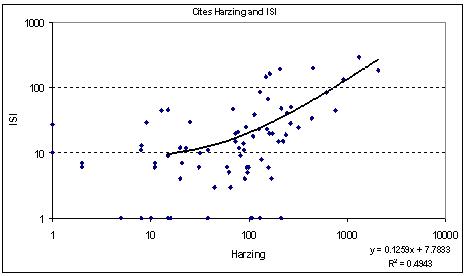

So far though these are rather aggregated

analyses, at the level of an author’s whole profile of work. By pooling

data across multiple authors, and looking instead at the level of

individual items we can examine how the relationships between the ISI,

HPoP and IPD scores operate at the level of individual publications.

Figure 2.6 shows the results for all the publications of a small

sub-sample of 15 academics taken from our 120 in the pilot survey. [We

are in the process of extending the item level analysis to cover all

authors in the pilot survey, so these early findings are indicative only

at this stage – although the patterns here are so strongly marked that

we do not expect them to change much on further analysis]. We

essentially repeat here the previous analysis, but at the level of

individual publications.

analyses, at the level of an author’s whole profile of work. By pooling

data across multiple authors, and looking instead at the level of

individual items we can examine how the relationships between the ISI,

HPoP and IPD scores operate at the level of individual publications.

Figure 2.6 shows the results for all the publications of a small

sub-sample of 15 academics taken from our 120 in the pilot survey. [We

are in the process of extending the item level analysis to cover all

authors in the pilot survey, so these early findings are indicative only

at this stage – although the patterns here are so strongly marked that

we do not expect them to change much on further analysis]. We

essentially repeat here the previous analysis, but at the level of

individual publications.

Figure 2.6: The relationship

between ISI and HPoP scores, and between ISI and IPD scores, for all the

publications of a subset of 15 academics drawn from the IPD

between ISI and HPoP scores, and between ISI and IPD scores, for all the

publications of a subset of 15 academics drawn from the IPD

Each mark represents the citation scores for a single publication. Graphs are log scaled.

(b)

(c)

(c)

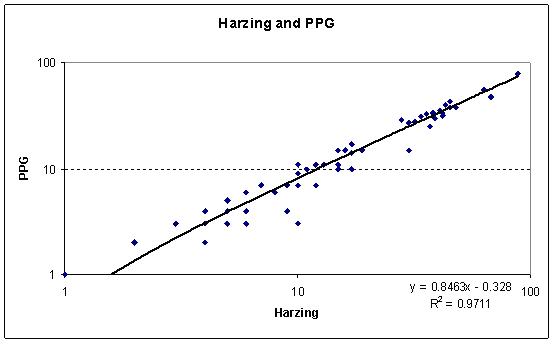

The previous patterns found are

strengthened. Figures 2.6a and 2.6b show that only around a quarter of

the score that individual social science publications get in the ISI

database can be explained in terms of HPoP

strengthened. Figures 2.6a and 2.6b show that only around a quarter of

the score that individual social science publications get in the ISI

database can be explained in terms of HPoP

/Google scholar citations, or in terms of

the manually cleaned and checked IPD scores (also including manually

checked Google Books scores). By contrast, Figure 2.6c shows that the

HPoP/Google Scholar scores for all publications included in the analysis

are very similar indeed to the checked IPD scores. Indeed the R squared

proportion of variance explained is 97 per cent, meaning that the two

indicators are clearly tapping the same phenomena. Interestingly,

although our analysis eliminated a good deal of double counting in the

HPoP/Google Scholar listings, none the less the checked IPD scores are

somewhat above the parity line here – reflecting the role of

Google Books in boosting item scores. The two indicators move closely in

step, but are not exactly the same. By contrast, the ISI citations

count for most social science publications is far less than the

HPoP/Google Scholar or IPD counts.

the manually cleaned and checked IPD scores (also including manually

checked Google Books scores). By contrast, Figure 2.6c shows that the

HPoP/Google Scholar scores for all publications included in the analysis

are very similar indeed to the checked IPD scores. Indeed the R squared

proportion of variance explained is 97 per cent, meaning that the two

indicators are clearly tapping the same phenomena. Interestingly,