Source: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20230519155707244

GLOBAL

You have been warned: A breakthrough in rankings is coming

In

a tweet

sent from Tashkent, Uzbekistan, after the closing of the IREG

Observatory on Academic Ranking and Excellence conference I wrote: “IREG

2023 clearly articulated that in the coming years nothing in the world

of rankings will be the same. The main word of the conference was

‘breakthrough’. We discussed where and when it will happen, and we

looked for its first signs…”

Since university rankings have been a hot issue in higher education

debates for a long time and several people have asked me about this

future breakthrough, I will try to explain what I mean.

A view from Central Asia

Far away from the traditional ranking conferences, Tashkent turned out

to be an excellent site for the IREG 2023 Conference. Once, its cities

of Samarkand and Bukhara were a key link on the Silk Road and now

Uzbekistan is a fast-developing country that has made education and

science the basis of its modernisation efforts.

The annual IREG conferences are the world’s only neutral place where

rankers, higher education experts and analysts as well as universities –

often represented by rectors – meet.

The issues discussed there often have a direct impact on rankings and their standards.

Judging by the feedback, IREG 2023 was a creative and refreshing event. Here are three characteristic comments:

• Laylo Shokhabiddinova, head specialist of the international rankings

department at Tashkent State Transport University, said: “From around

the world, we have come to share our experiences, ideas and insights on

ranking in higher education. It has been an eye-opening experience for

me, and I am grateful for the chance to connect and collaborate with

such an esteemed group of professionals. As universities continue to

navigate a rapidly changing landscape, it is more important than ever to

stay connected and learn from each other.”

• Alex Usher, president of Higher Education Strategy Associates, Canada,

stated: “One of the most interesting ranking discussions I’ve heard in

years. The difference in discourse around rankings after leaving a rich

country is huge – here there is much less about marketing and much more

about system control or benchmarking.”

• Komiljon Karimov, first deputy minister of higher education, science

and innovation in Uzbekistan, commented: “I often participate in various

conferences and seminars, but I have not met such a substantive and

engaged discussion for many years.”

The conference in Tashkent showed how pragmatic and hopeful expectations

about rankings are among universities and governments of countries

outside Europe and North America.

They need the rankings as a tool to monitor implementation of reforms in

higher education, to improve the quality of education and not for the

sake of prestige. But this aspect has already been analysed by Usher in

his highly recommended blog under the title “

Rankings Discourses: West, East and South”.

Historical background

So, what new trends and ideas emerged in Tashkent about the global

rankings landscape? To properly interpret new trends, we need to go back

to the turn of the century and the beginning of the era of

massification and globalisation of higher education. The UNESCO World

Conference of 1998 was not able to properly describe this phenomenon.

There was simply no comparable data available. It’s hard to believe, but

the situation has not changed much since.

Concern about this state of affairs was sounded by Philip Altbach 10 years ago in a

University World News article, “

Long-term thinking needed in higher education”,

in which he regretted that none of the global or regional organisations

with the necessary potential and prestige (the UN, UNESCO and the OECD)

had taken the necessary action on data collection.

He even went so far as to say that they had “abdicated” responsibility

from the roles they should perform. He wrote: “There is a desperate need

for ongoing international debate, discussion and regular data

collection on higher education. At present, we have only a fragmented

picture at best.”

Similarly unsuccessful in setting up an updated database was the

European Union. Projects financed by the EU, such as the European

Tertiary Education Register (ETER) had been undertaken but never fully

implemented. This is why rankings, first national, then international,

have been a discovery, introducing ‘countability’ to higher education.

The first conference of an international group of ranking experts (from

which IREG was born) was in Warsaw in June 2002. There were no

international rankings yet, but national rankings (including

US News

Best Colleges in the USA, Maclean’s in Canada, CHE in Germany and

Perspektywy in Poland) were such a fascinating phenomenon that Jan

Sadlak from UNESCO-CEPES and Andrzej Kozminski, rector of Kozminski

University, invited a group of ranking creators to a debate in order to

exchange information. I spoke there about

Perspektywy’s first 10 years in ranking.

The next meeting, in Washington DC, in 2004, included Nian Cai Liu with

his brand new Shanghai Ranking. At the 2006 meeting in Berlin, the IREG

group adopted the famous “Berlin Principles on Ranking of Higher

Education Institutions” which introduced quality standards for rapidly

emerging new rankings.

Had UNESCO or any other international organisation been able to collect

data globally and annually update reliable information on higher

education, international rankings would probably never have gained such

momentum and importance. But politicians, or rather bureaucrats, have

failed, and not for the first time.

As a result, the short history of modern rankings (40 years of national

rankings and 20 of international ones) has seen them gain an inflated

role which they did not initially aspire to. It is a fascinating history

of exploration, confusion and rivalry.

Don’t break the thermometer

We all see and feel that the world is changing and that it is changing

in many ways. Geopolitical forces are shifting and technological

advancements and artificial intelligence are both promising and scary.

All this has a strong impact on higher education and, consequently, on

the academic rankings. The rankings landscape is changing quickly too.

A new approach to rankings has emerged in the form of the impact

rankings, reflecting university contributions to social goals. The range

of regional and ‘by subject’ rankings have also grown.

At the same time, criticism of rankings has intensified, particularly

from the European higher education and research community. There are new

initiatives (the

Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment to name one) which are searching for new conceptual approaches and tools for university assessment.

IREG Observatory welcomes the search for ever better tools to measure

and evaluate excellence in research and higher education. However, we

see no need to breed a ranking phobia in the process. Assessment and

rankings serve different purposes. IREG expressed this very clearly in

its position paper, “

Assessment and rankings are different tools”, published last December.

Higher education around the world faces many difficult problems, but

rankings are not the cause of them. Rankings are like a thermometer that

signals various academic illnesses. But neither sickness nor fever

disappears when we break the thermometer. The same applies to rankings.

At the countless ‘summits’ organised almost weekly by the major ranking

players, the audience is told that the rankings and methodologies are

approaching the pinnacle of human achievement, and that the answer to

every university rector’s dreams is to purchase a ‘marketing package’, a

kind of miracle medicine.

It is not for nothing that some now consider the big ranking

organisations to be little more than ‘prestige-selling companies’ rather

than just a rankings provider, with rankings serving merely as the

‘cherry on the cake’.

Big data

There can be no meaningful analysis without good data, data that meets

the agreed standard, that is properly collected, externally validated,

updated at least once a year, if not more frequently, and is widely

available though not necessarily free, because quality costs. The fees,

however, should be reasonable.

Such data, however, cannot be obtained without the cooperation of

national education authorities. In turn, they must collect such data for

the efficient realisation of their public policy and economic strategy.

The data collected directly from universities by ranking organisations

and adjusted to their requirements have many imperfections that have

been well identified.

This applies to QS,

Times Higher Education and other

organisations that use surveys sent to and collected from universities.

Of course, when no other options are available, flawed data serves

better than none at all. However, let me point out that better

databases, anchored in national systems, have already appeared and, year

by year, are increasingly available.

M’hamed el Aisati, vice-president at Elsevier, and an analyst endowed

with an impressive “ranking intuition”, emphasised in his speech in

Tashkent the growing need for big data platforms to evaluate the impact

of research, its visibility, academic collaboration and innovation.

He then presented the first already tested and operational national

research evaluation platforms which are being used in Japan and Egypt.

What is a national research evaluation platform? As Aisati explained:

“It is a big data platform that provides a knowledge network to support

high-value decisions. It is a knowledge network that provides an

integrated view of relevant research data, ensuring that high-value

client decisions are based on an inclusive, truthful and unbiased view

of their country’s research ecosystem.”

Such a platform is modular. It collects dispersed data, including

digitisation. Non-English language data is being translated into

English. Linking and profiling of references as well as automatic

classification and metrics are provided.

In less specialised language: the big data national research evaluation

platforms cover the entire research output of Japan and Egypt, including

their academic characteristics. Hearing this at the IREG 2023

Conference, Professor Piotr Stepnowski, rector of the University of

Gdansk in Poland, said in an emotional outburst: “This will radically

change evaluation of individual countries in world science!”

Yes, it will! In fact, it already signals the beginning of a

‘breakthrough’, the word that best describes the essence of the

discussion in Tashkent.

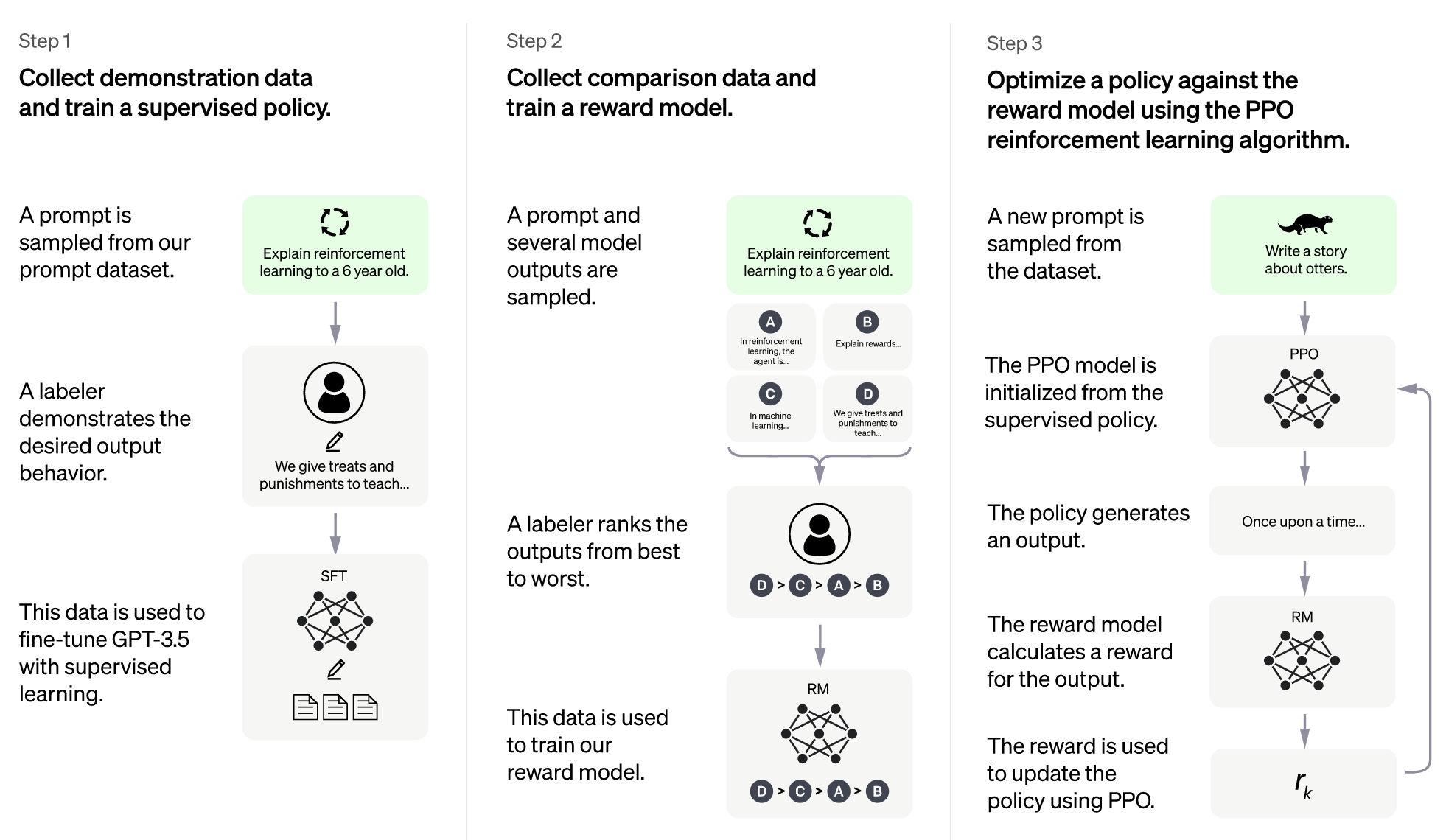

The role of AI

The subject of big data has appeared in various ranking-related

conversations for over a dozen years. It is obvious that the global

‘data ocean’ on science and higher education can create new analytical

possibilities and, consequently, new solutions in the ranking area. By

the way, ‘data ocean’ was one of the key phrases of the IREG 2019

Conference in Bologna.

But the excitement about this potentially revolutionary technology has

been effectively dampened by the so-called ‘artificial intelligence

winter’. It was impossible to meet the huge expectations presented by

the first AI algorithms because two things were still missing: data that

could be sent in bulk, and computing power of sufficient capacity.

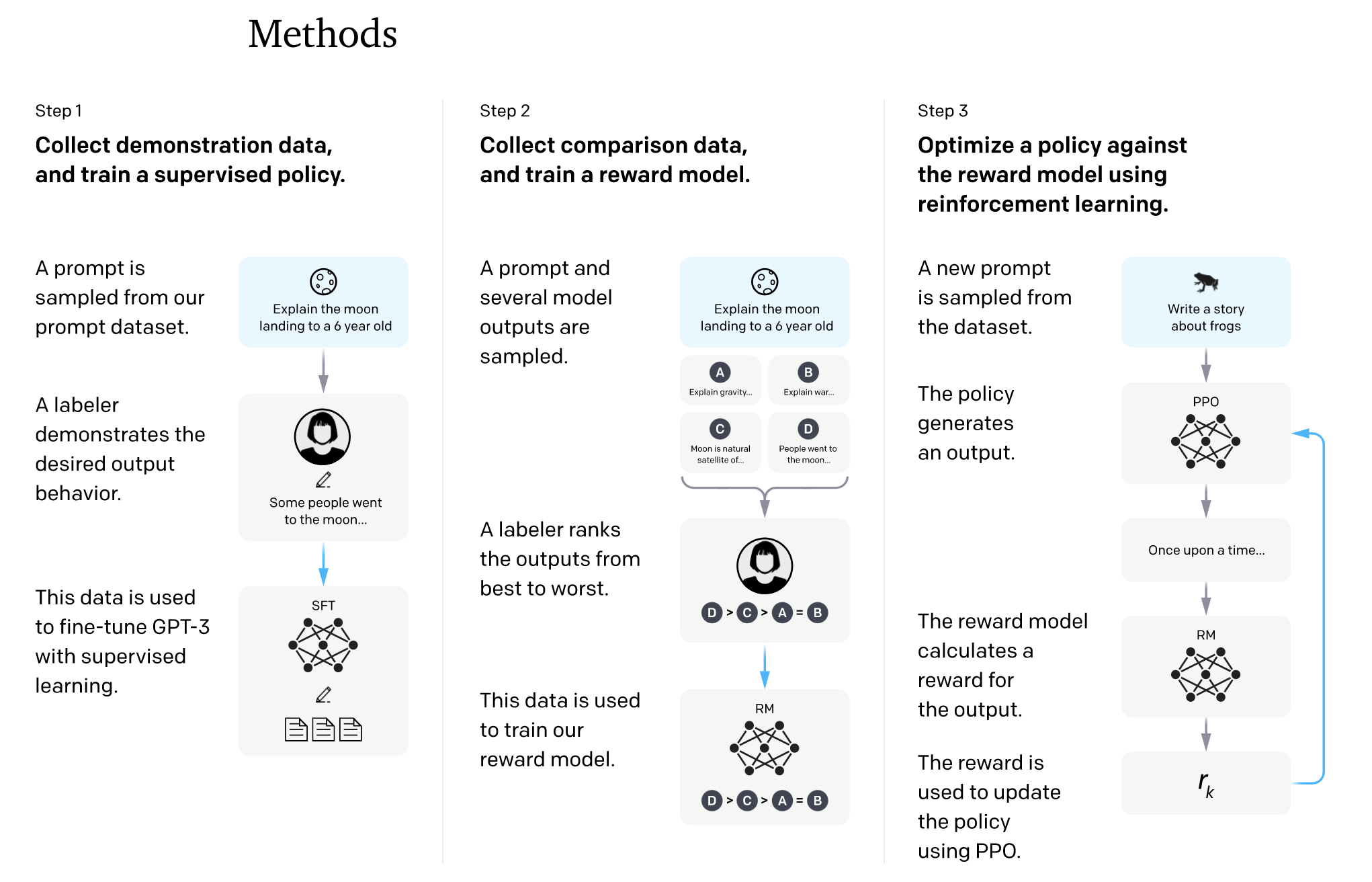

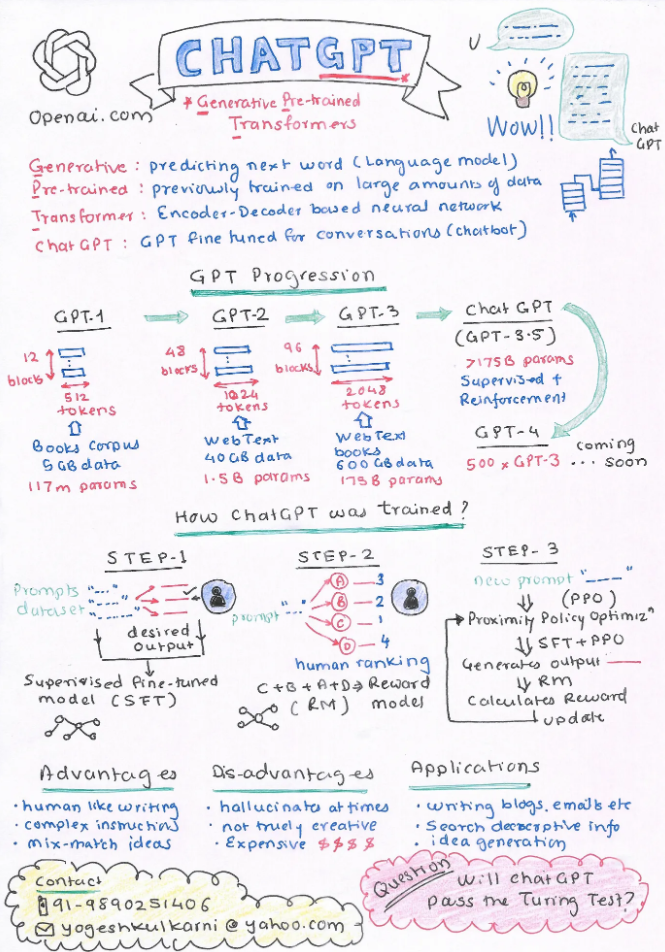

Only in the last 10 years has computing power, as well as very fast,

high-bandwidth communication, like the 5G systems, allowed artificial

intelligence to be used effectively. The emergence of ChatGPT and the

rapid spread of this application has brought millions of people closer

to the practical implementation of AI.

At the same time, in many countries solid database systems covering

higher education and science have been created (the author of this text

was the leader of the team that prepared the design of such a system in

Poland, currently functioning under the name

POL-on).

So we now have both the data and the desired computational power. It

would be naive not to expect that a platform based on giant higher

education databases and AI algorithms would soon make an appearance in

the university rankings field. The question is: ‘Who will be the first

to come up with such a ranking platform or application?’.

Waldemar Siwinski is president of the IREG Observatory on Academic

Ranking and Excellence, and founder of the Perspektywy Education

Foundation, Poland.